maitreyaravenstar@gmail.com

The Last Knickerbocker in New York, 2025

One of four selected winners of the Periclean Scholars Thesis Award for Skidmore College’s graduating class of 2025

Winner of Golden Acorns Award, John B. Moore Documentary Studies Collaborative, 2025

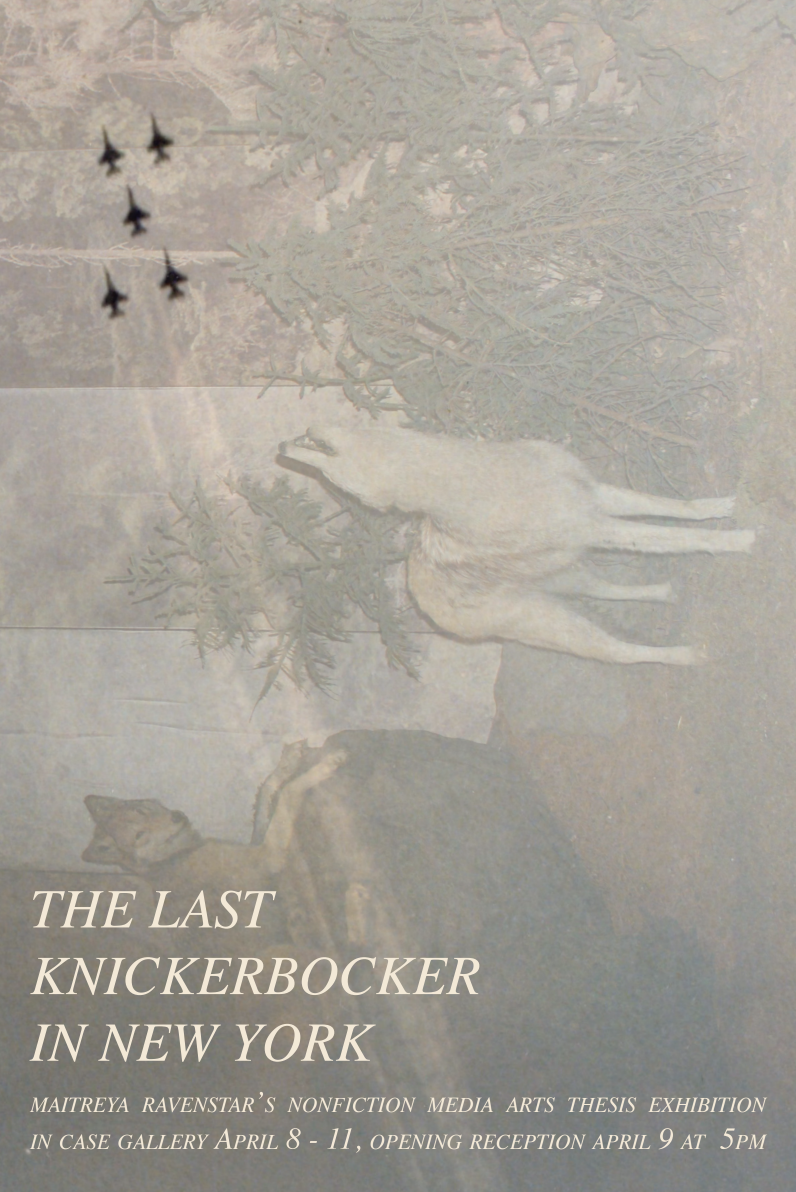

Installation in Case Gallery, Saratoga Springs, NY

Film Unsaid, Unseen screened at Picture Lock One in Troy, NY

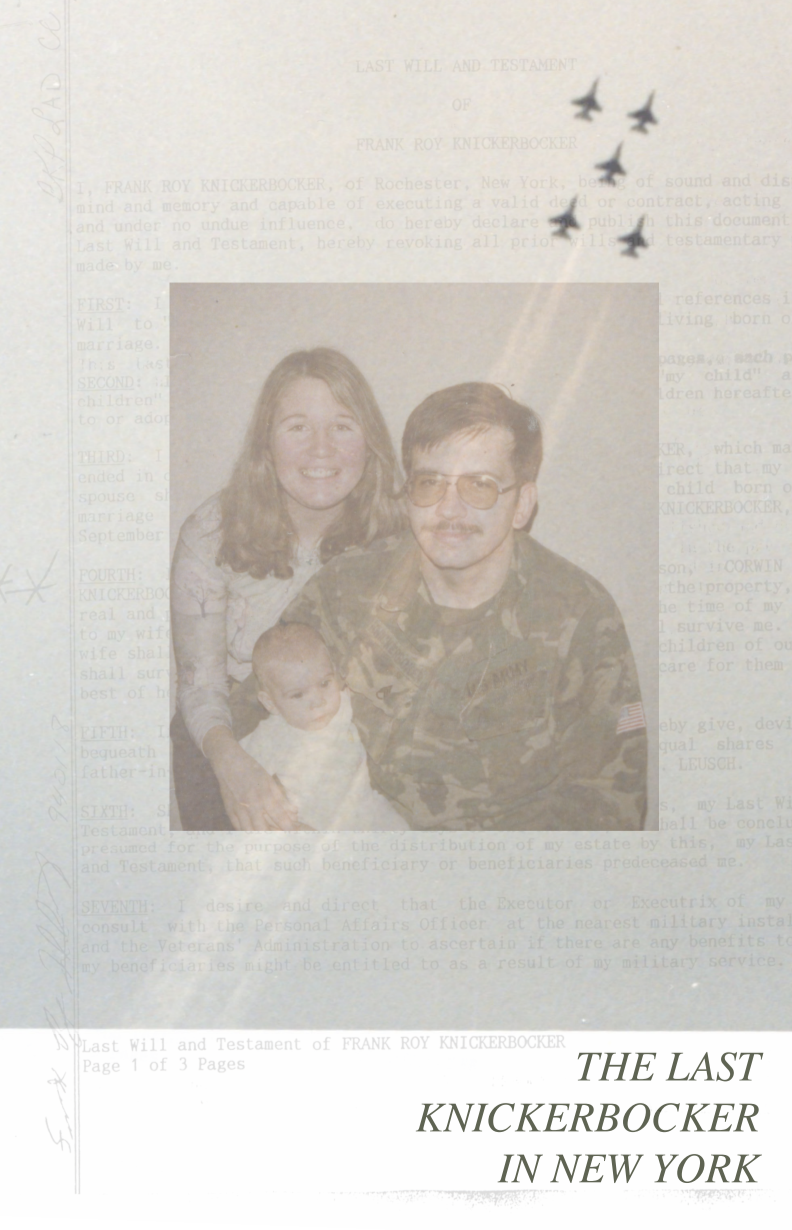

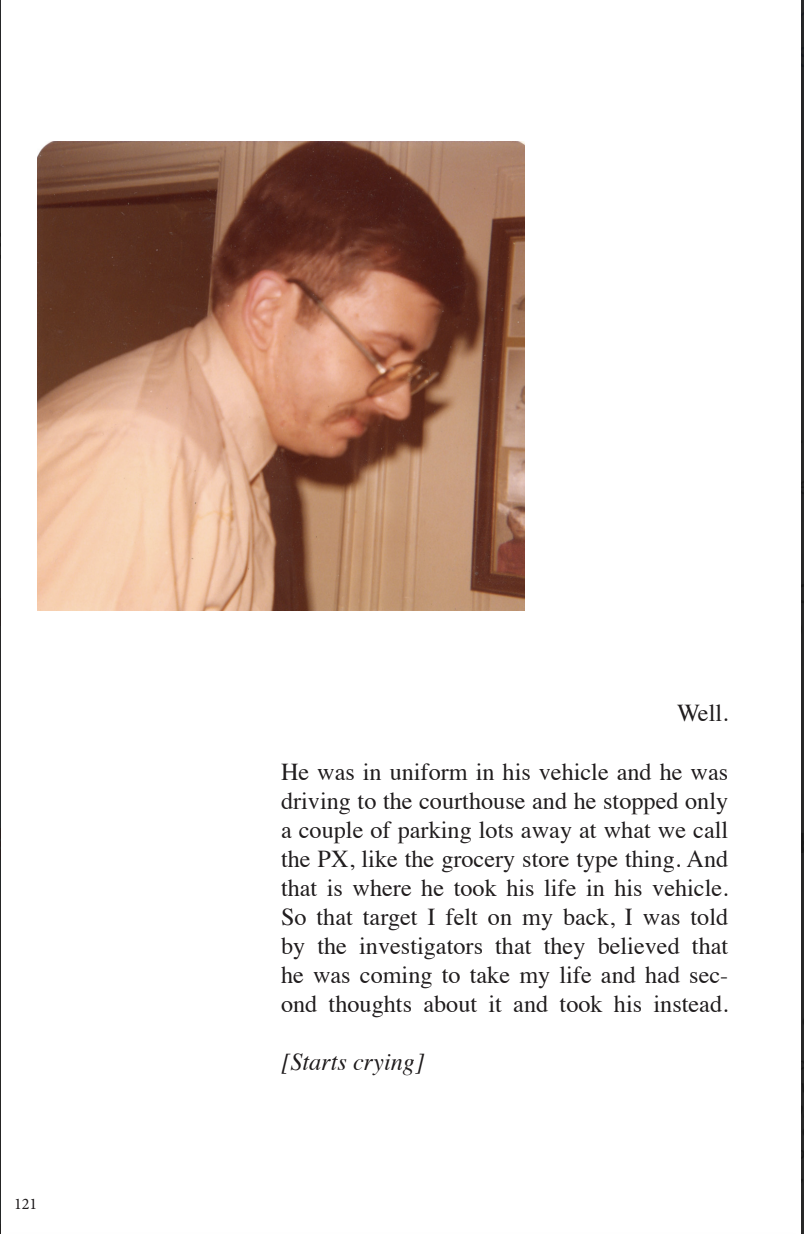

The Last Knickerbocker in New York is an interdisciplinary oral history project that explores how to creatively communicate a portrait of a person posthumously, questioning the multiplicity of truth in memory work and the role of the editor in archive generation. I spent the semester learning about Nick Knickerbocker, my paternal grandfather, who took his own life to avoid incarceration for nonviolent crimes. The project takes the form of a 160 page book, an installation of archival photos and objects and new photographic prints, and a reflective experimental film.

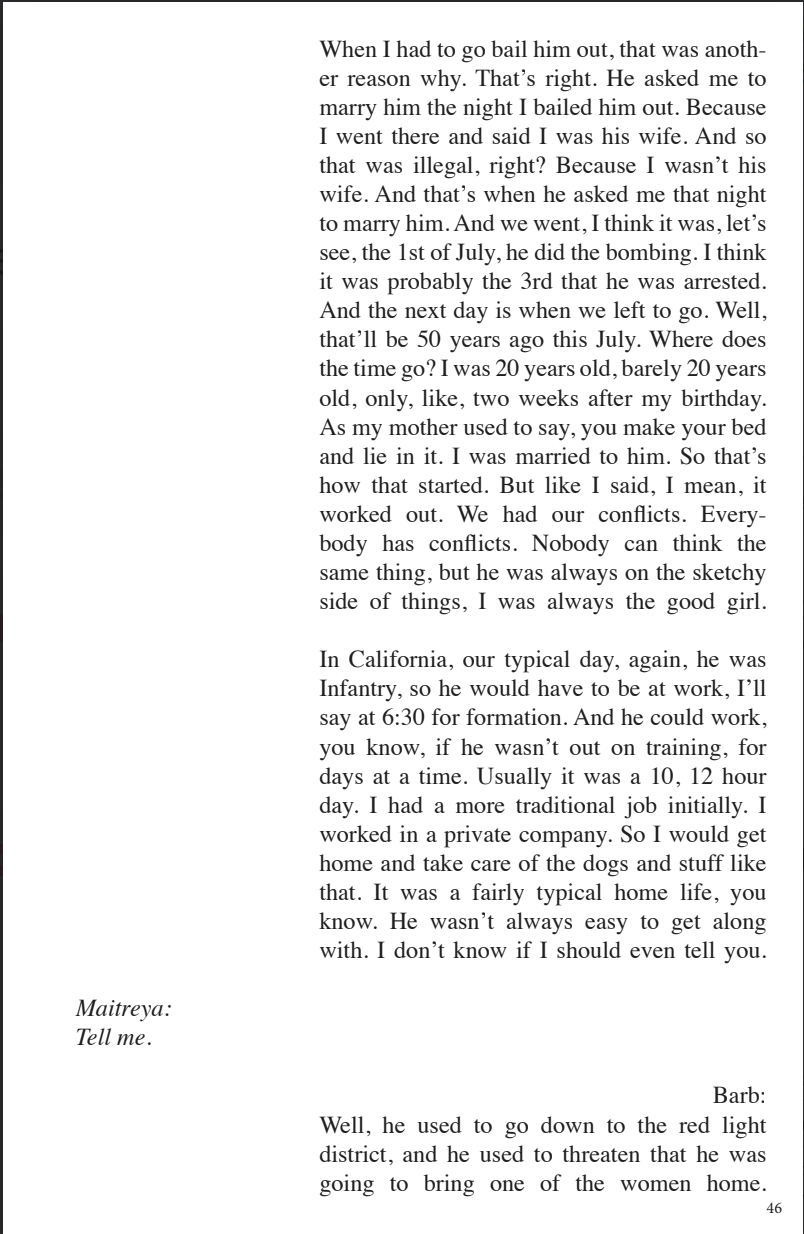

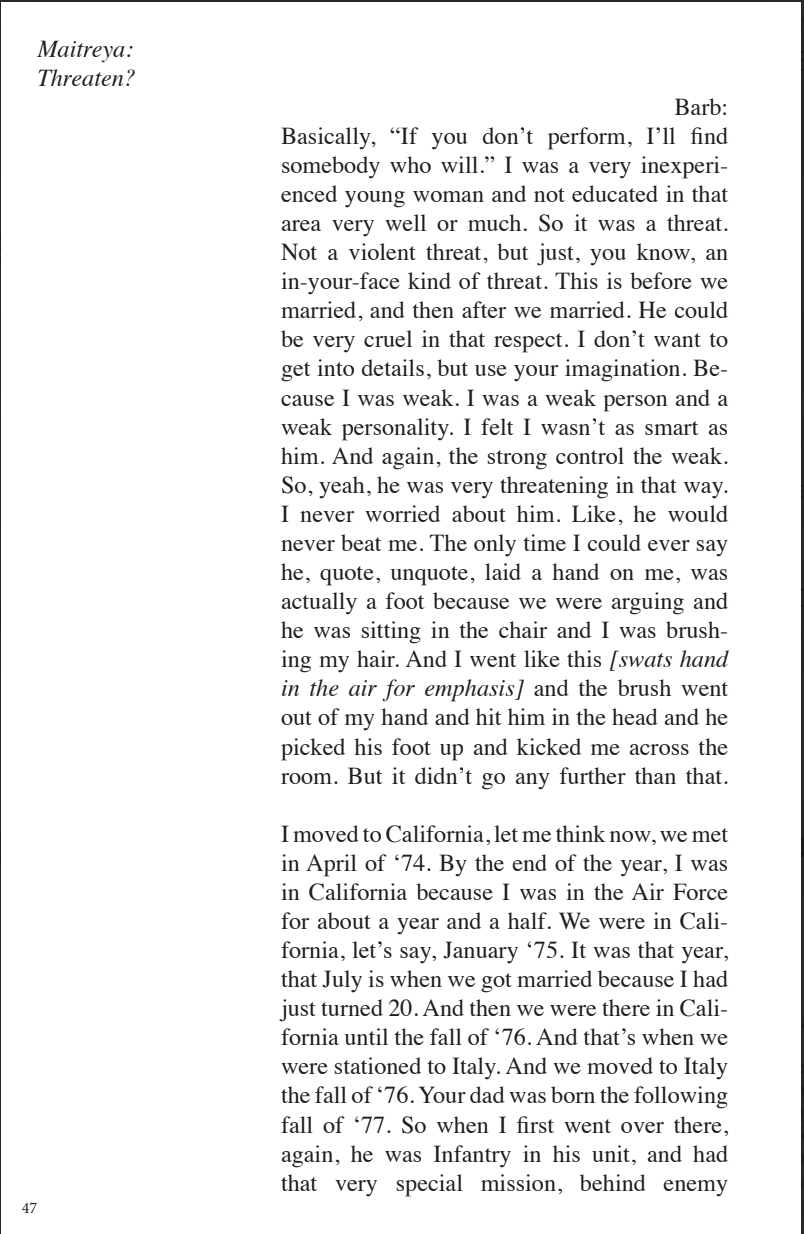

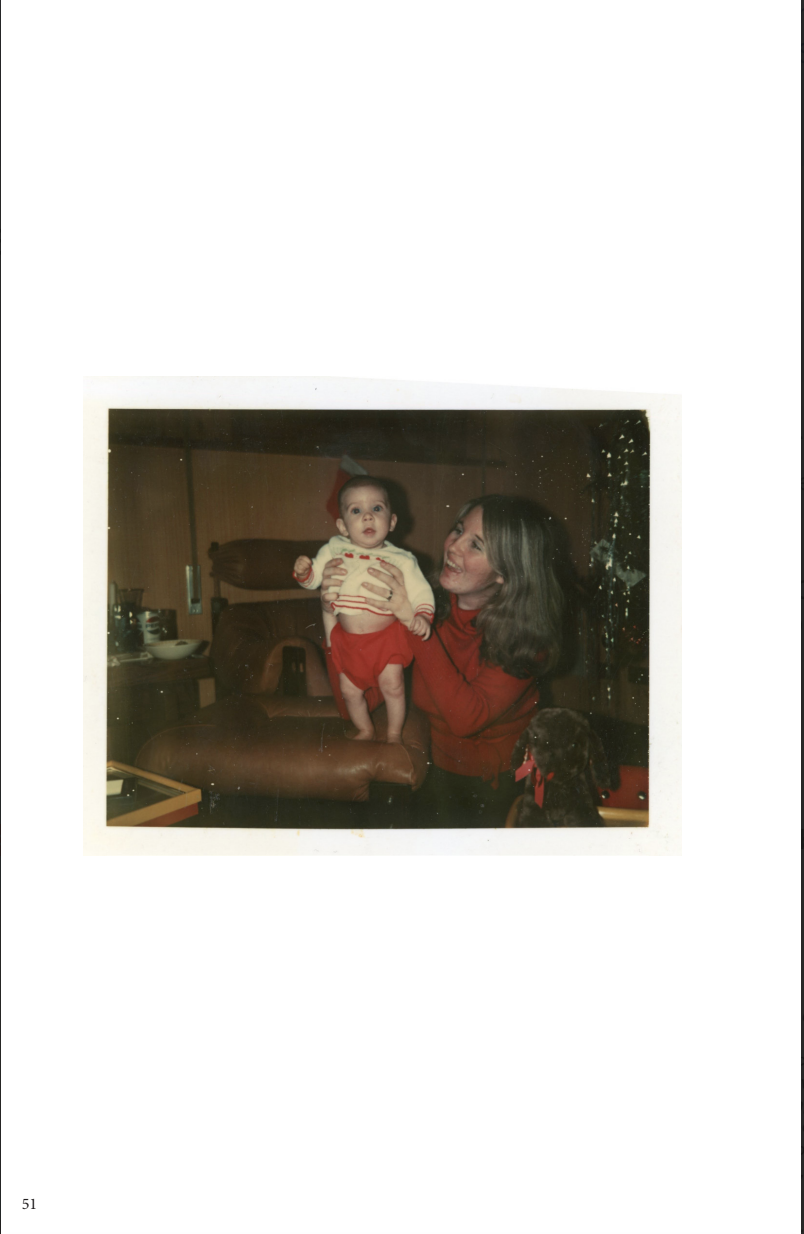

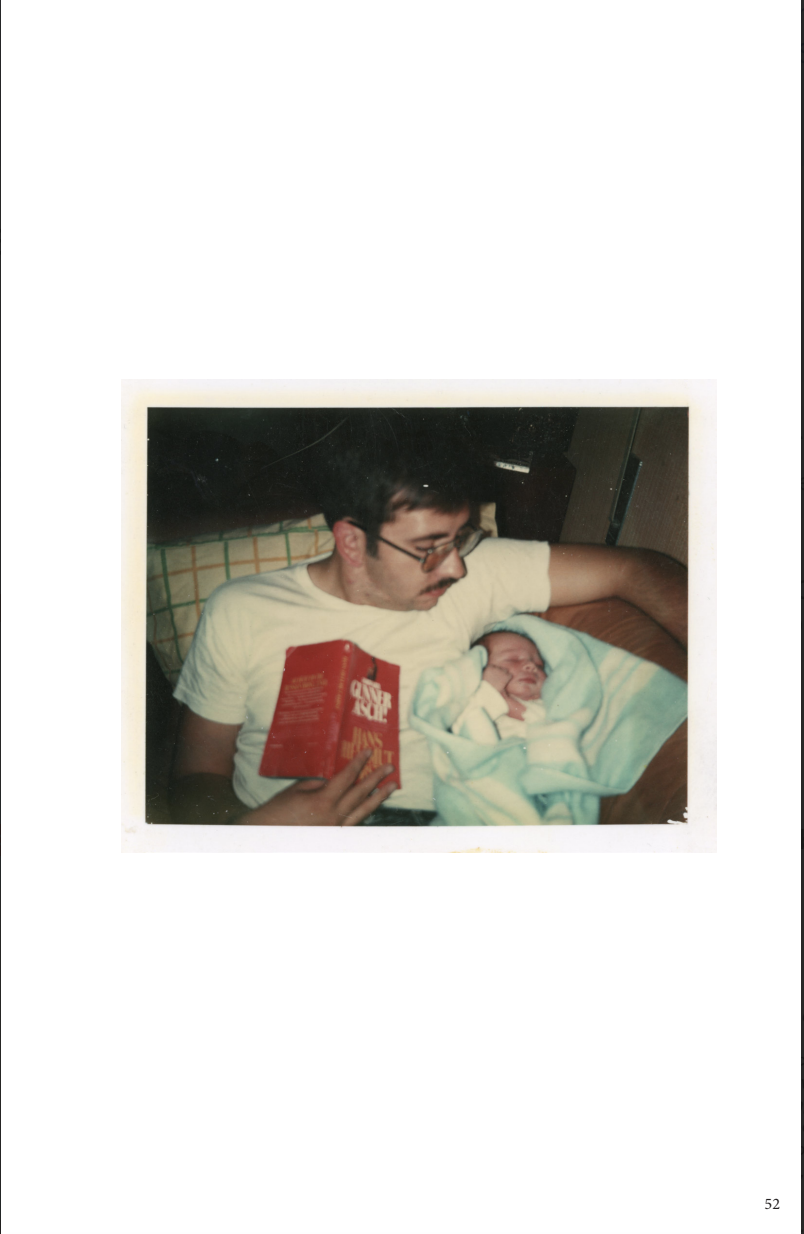

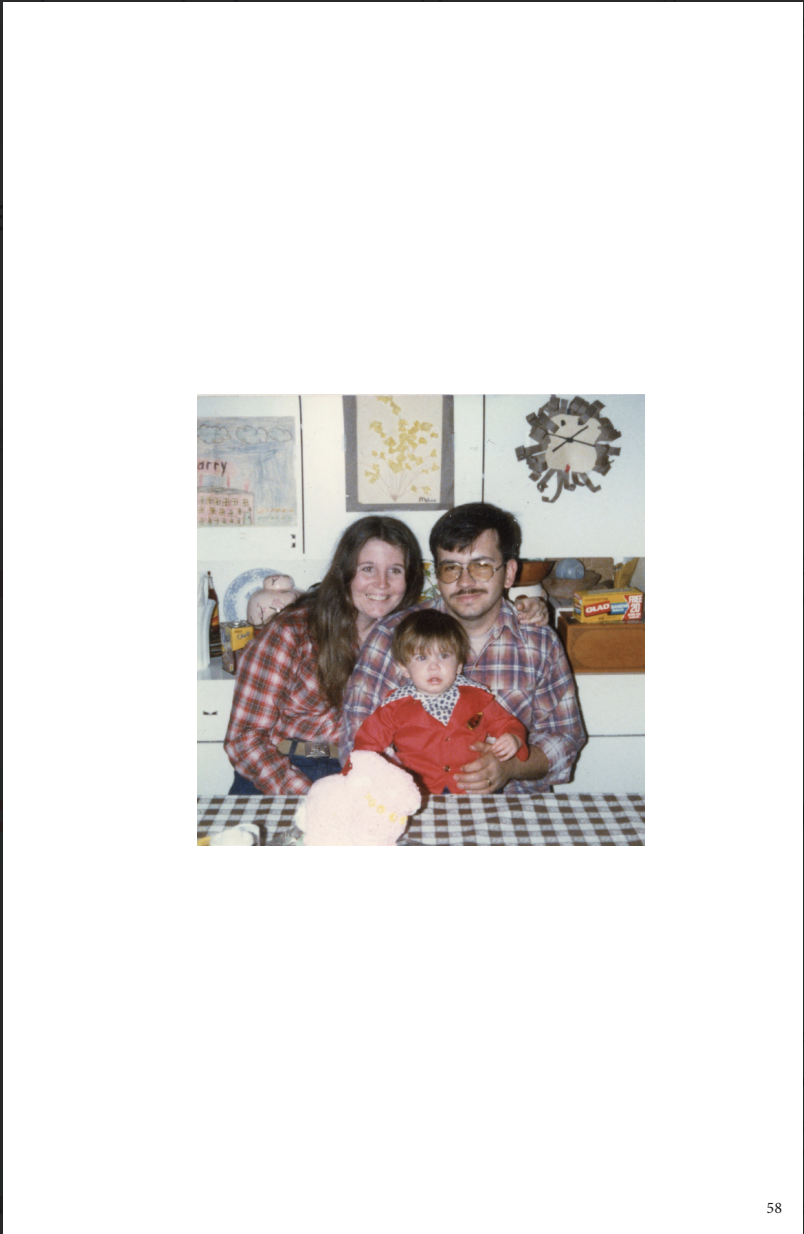

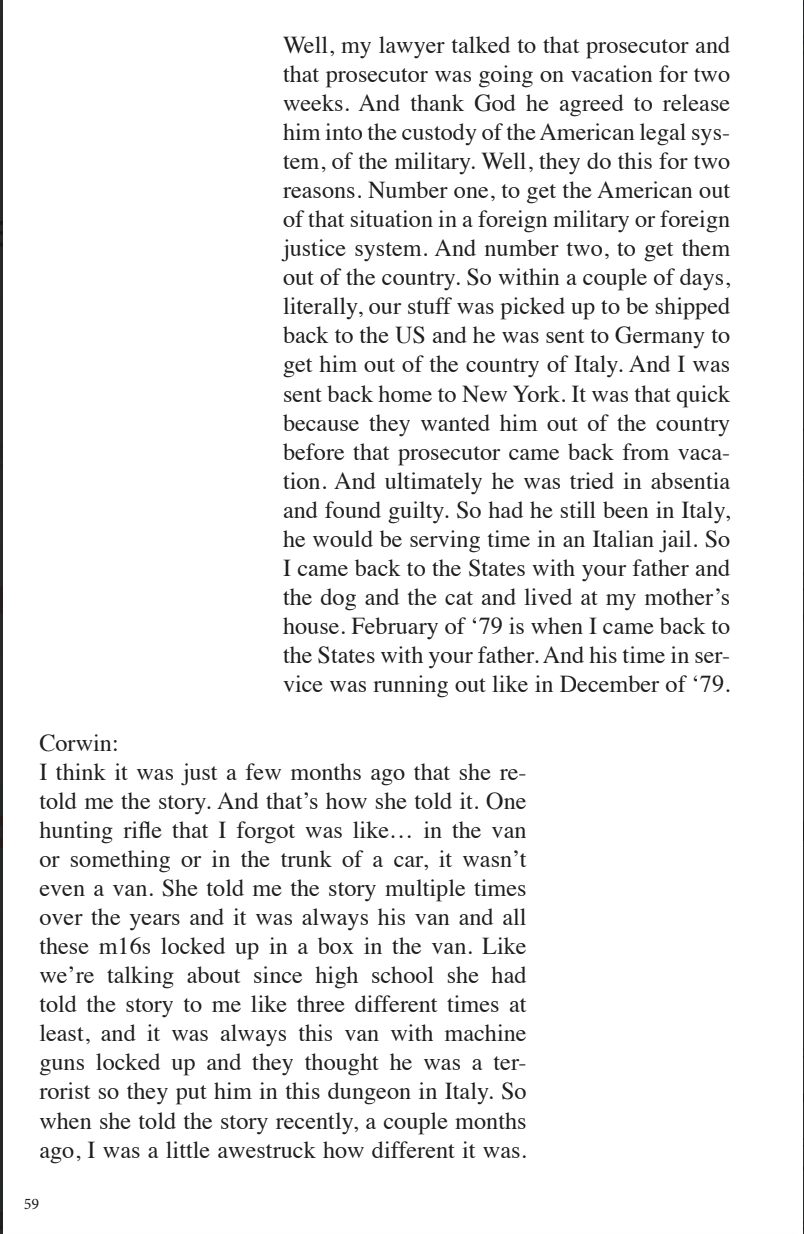

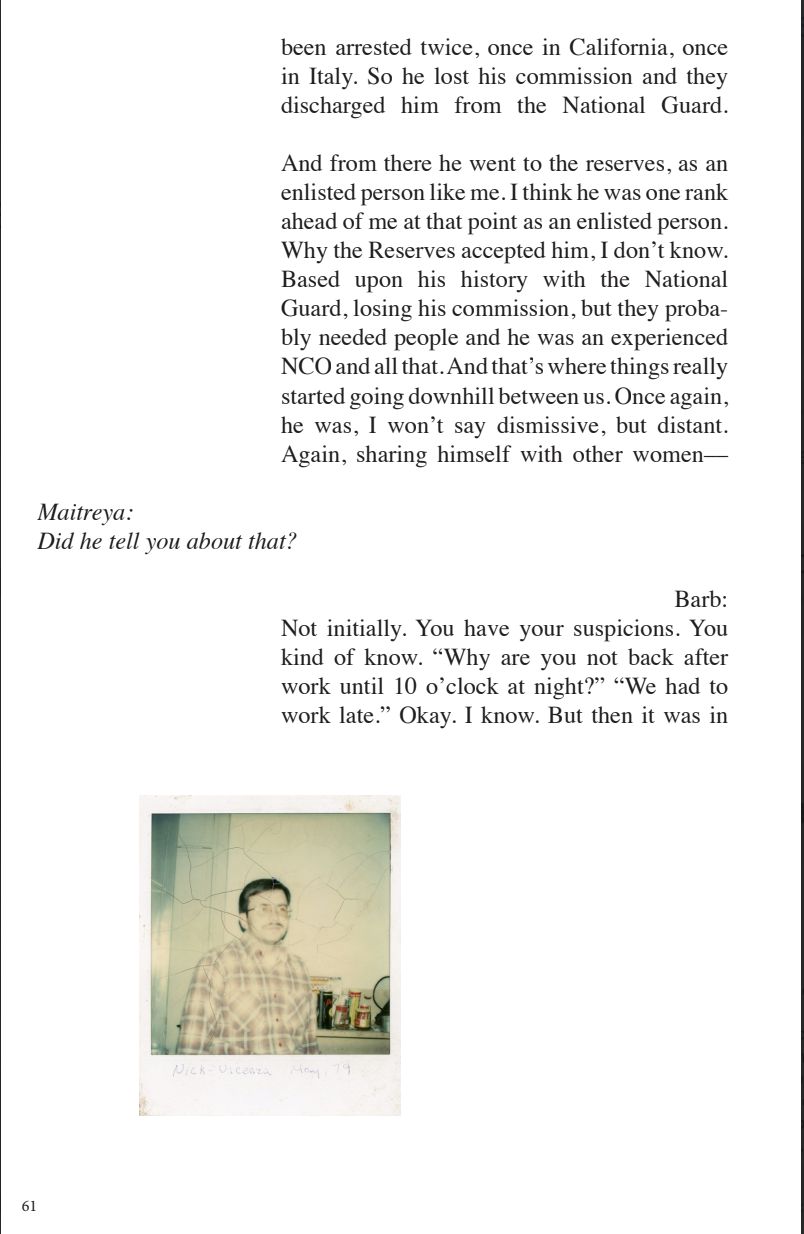

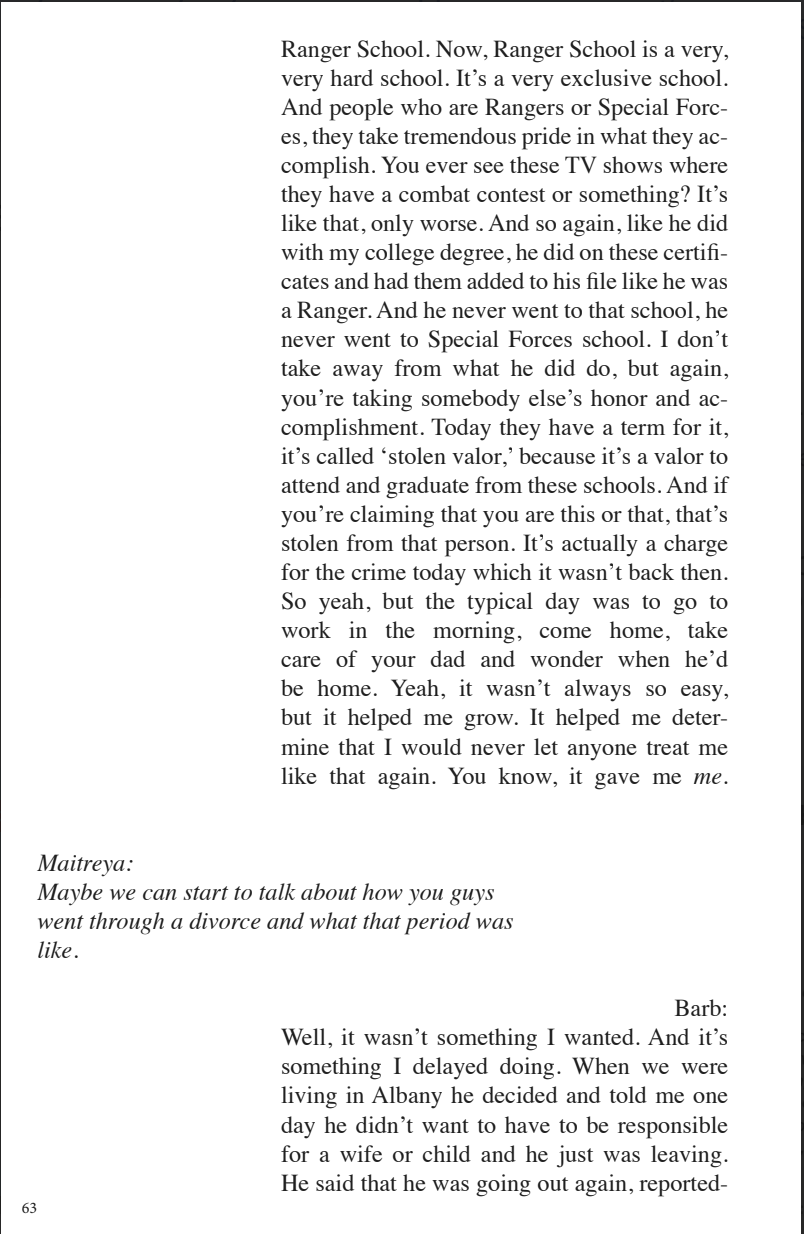

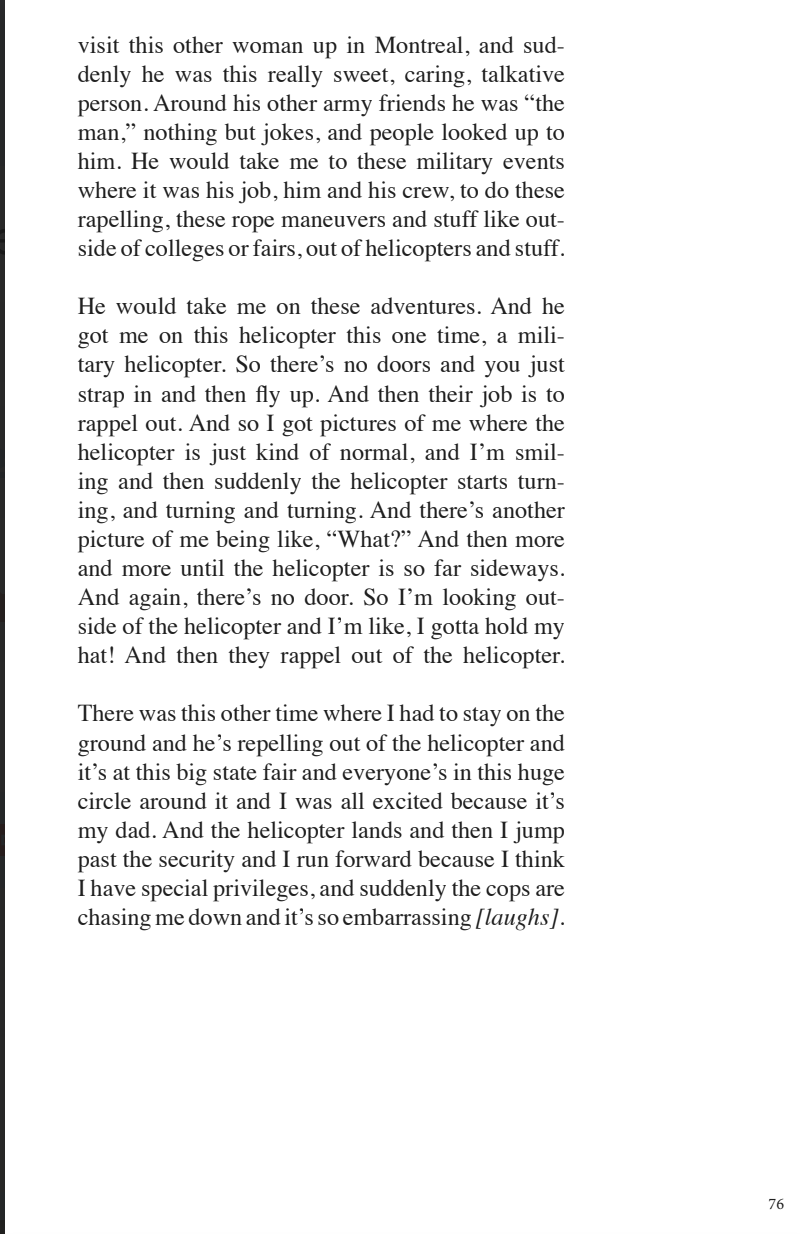

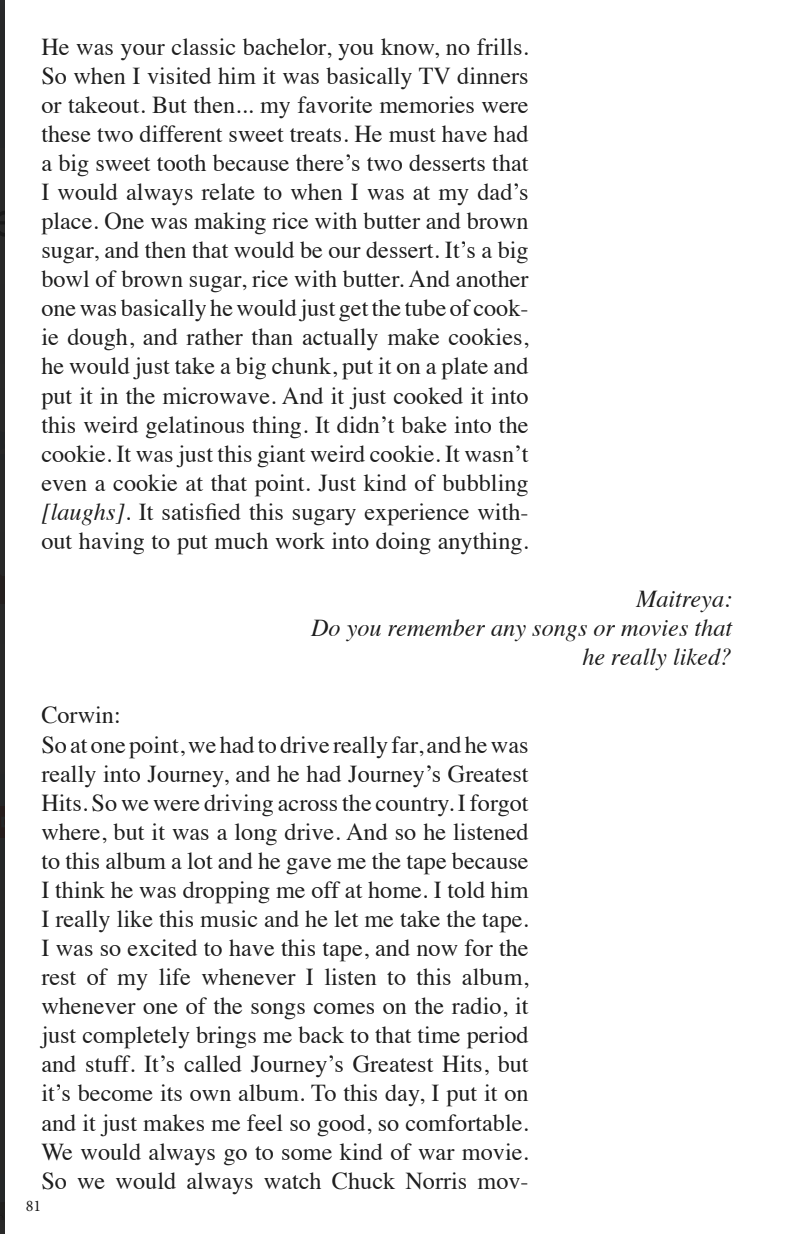

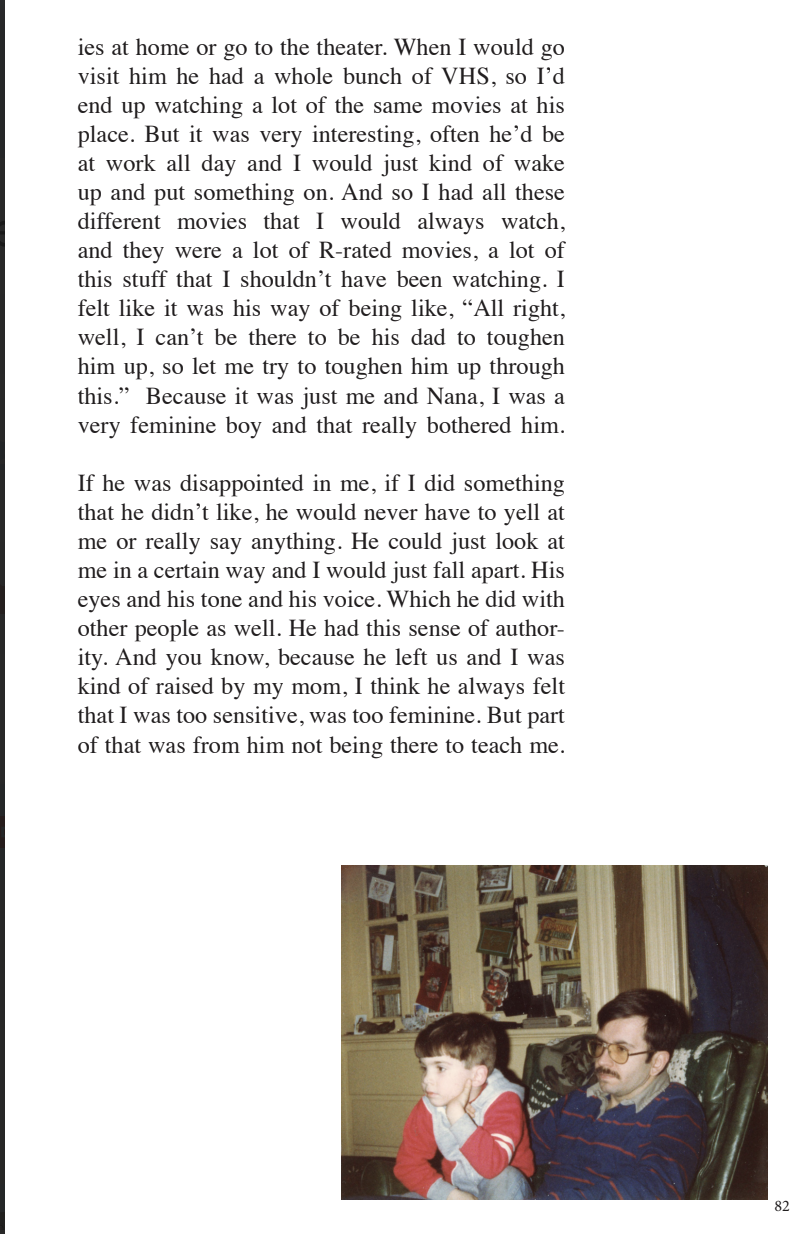

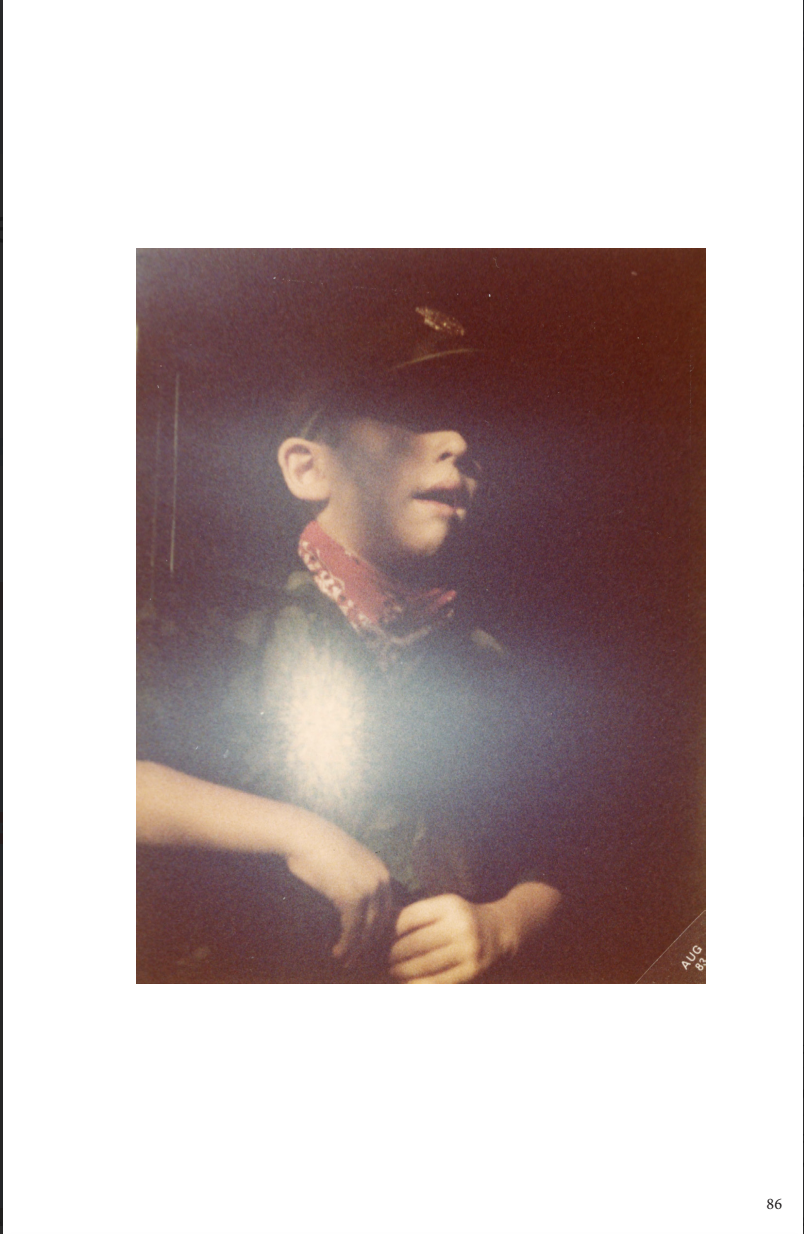

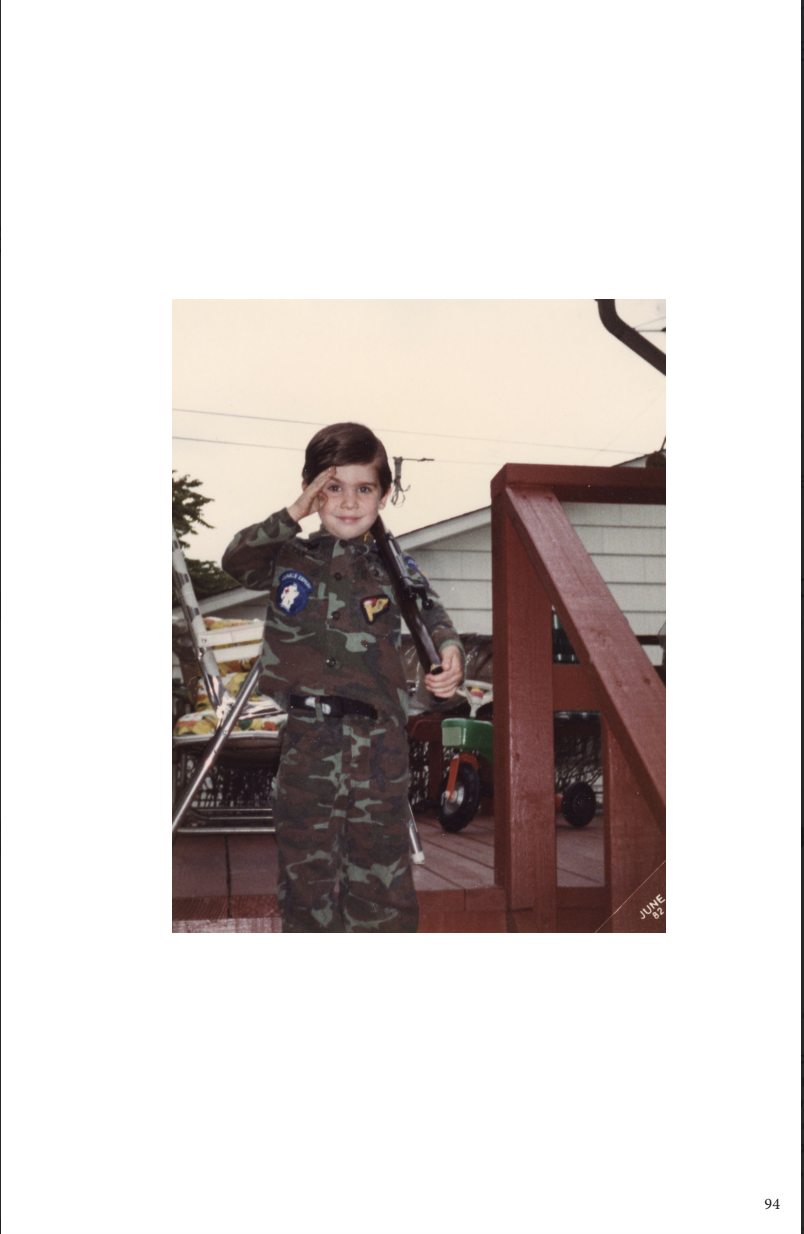

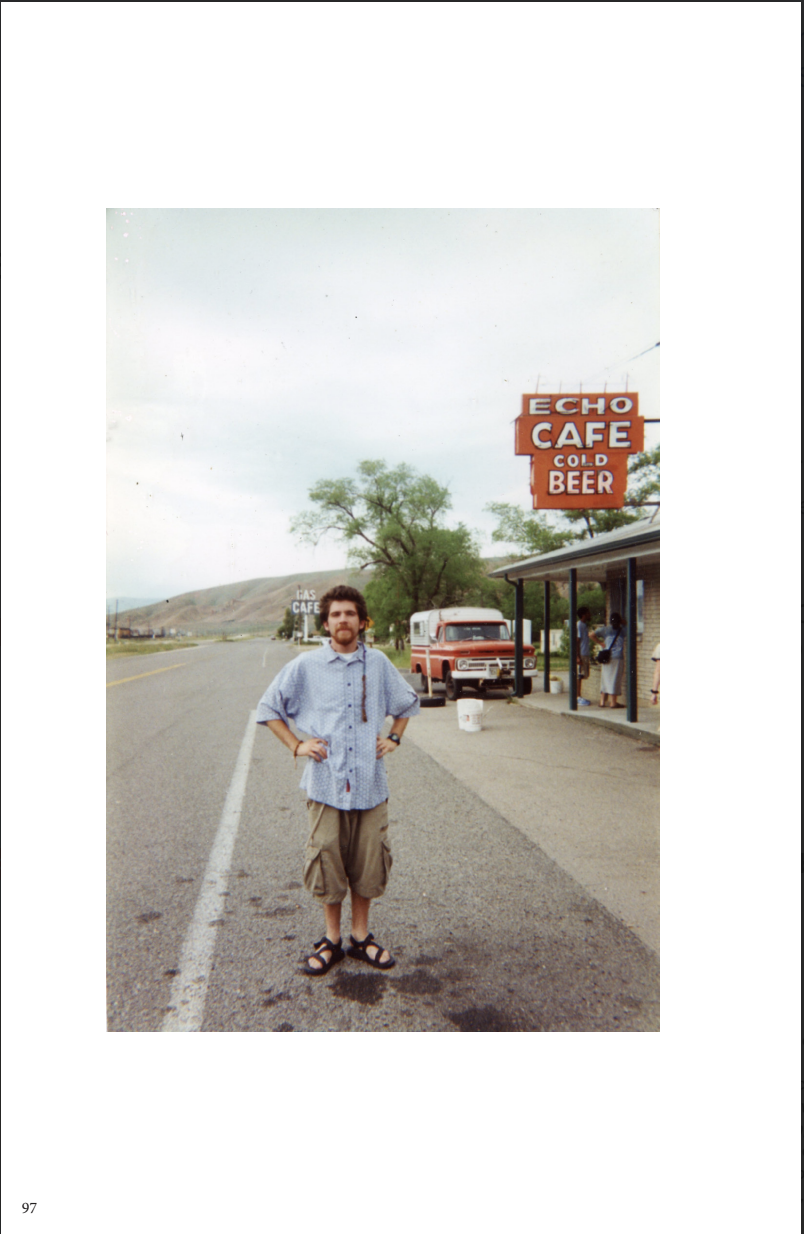

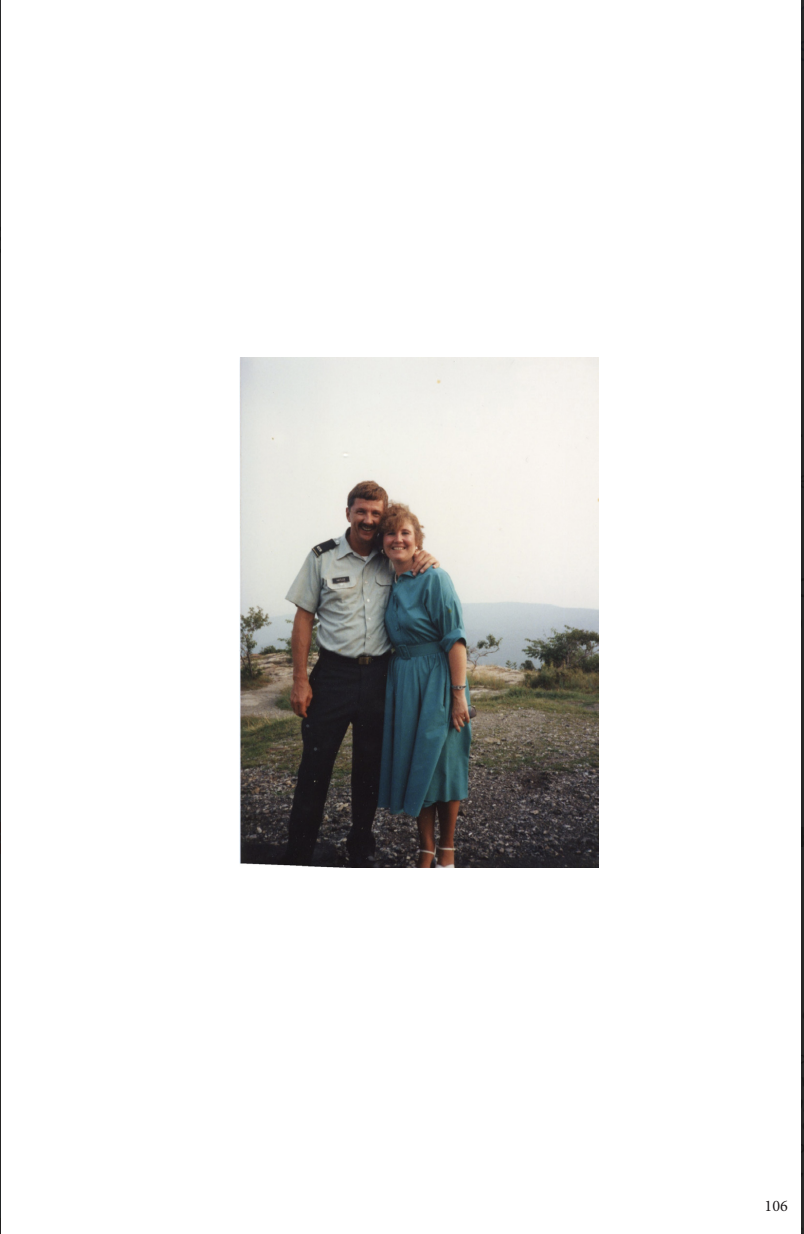

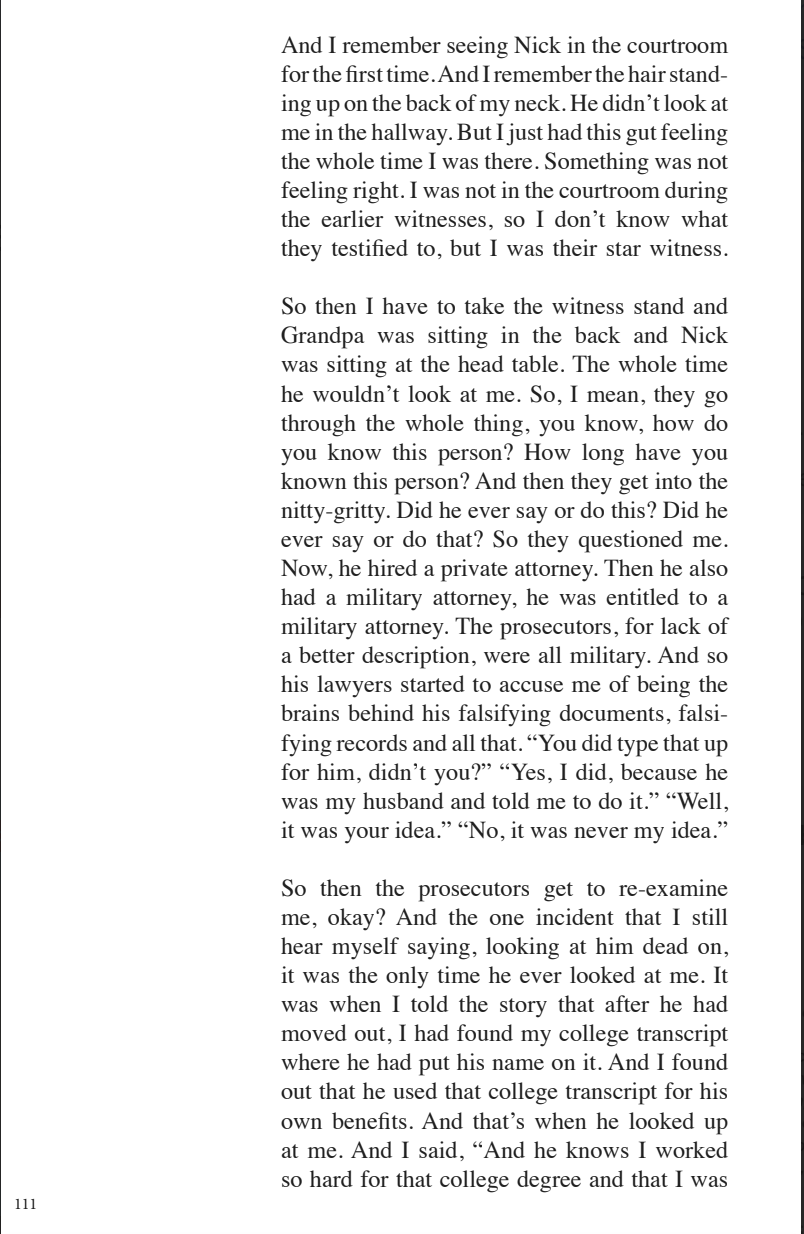

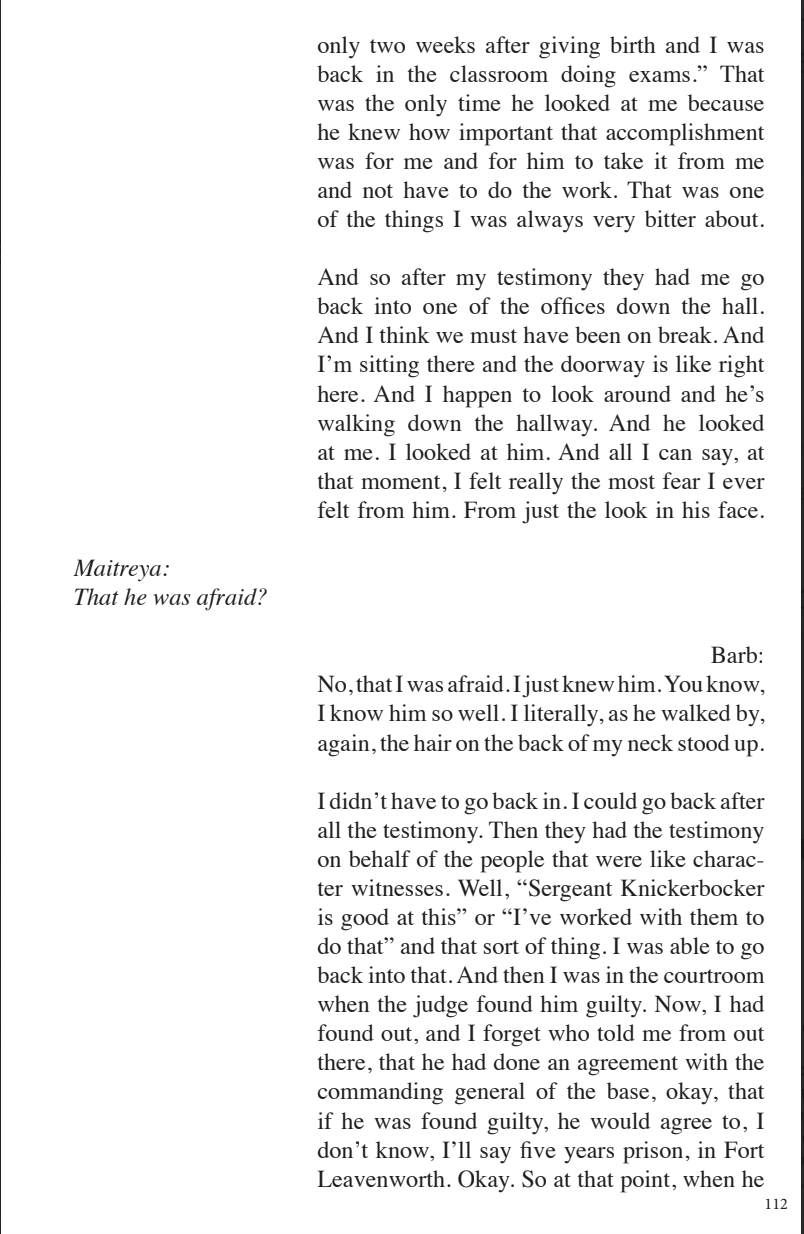

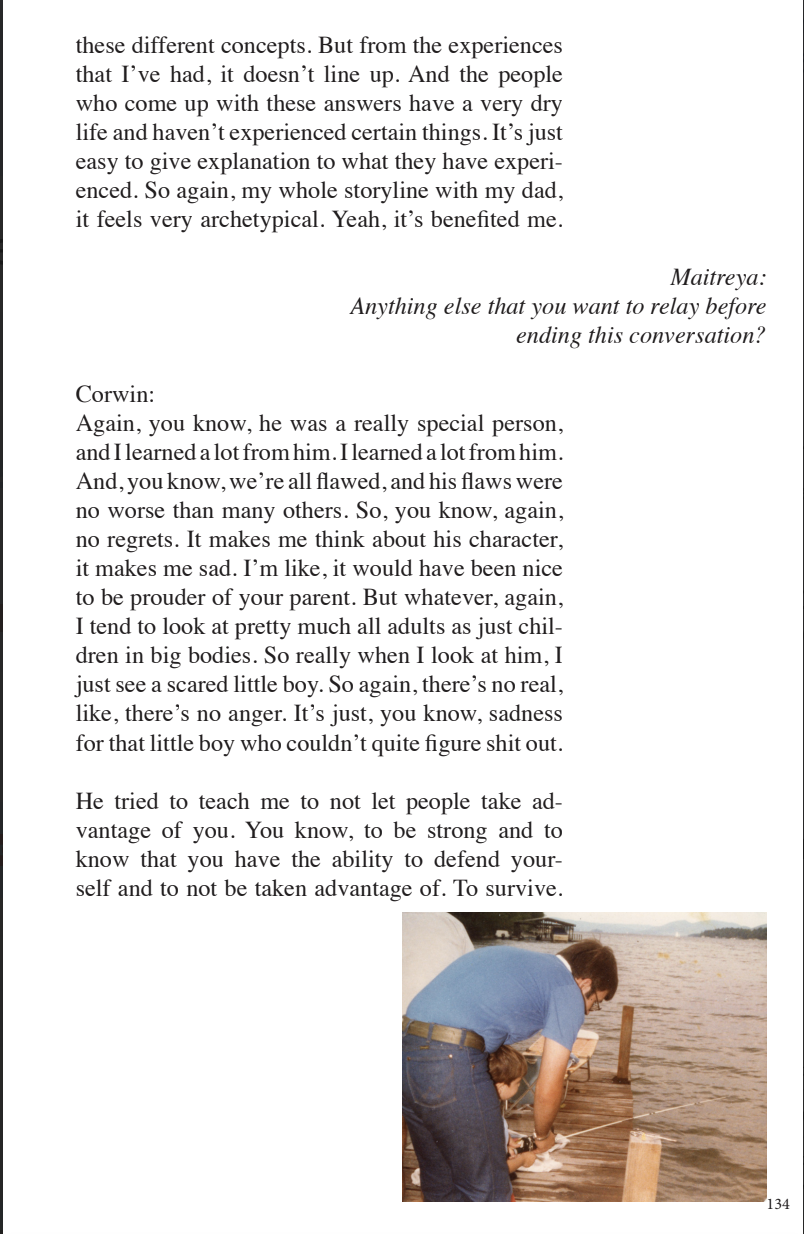

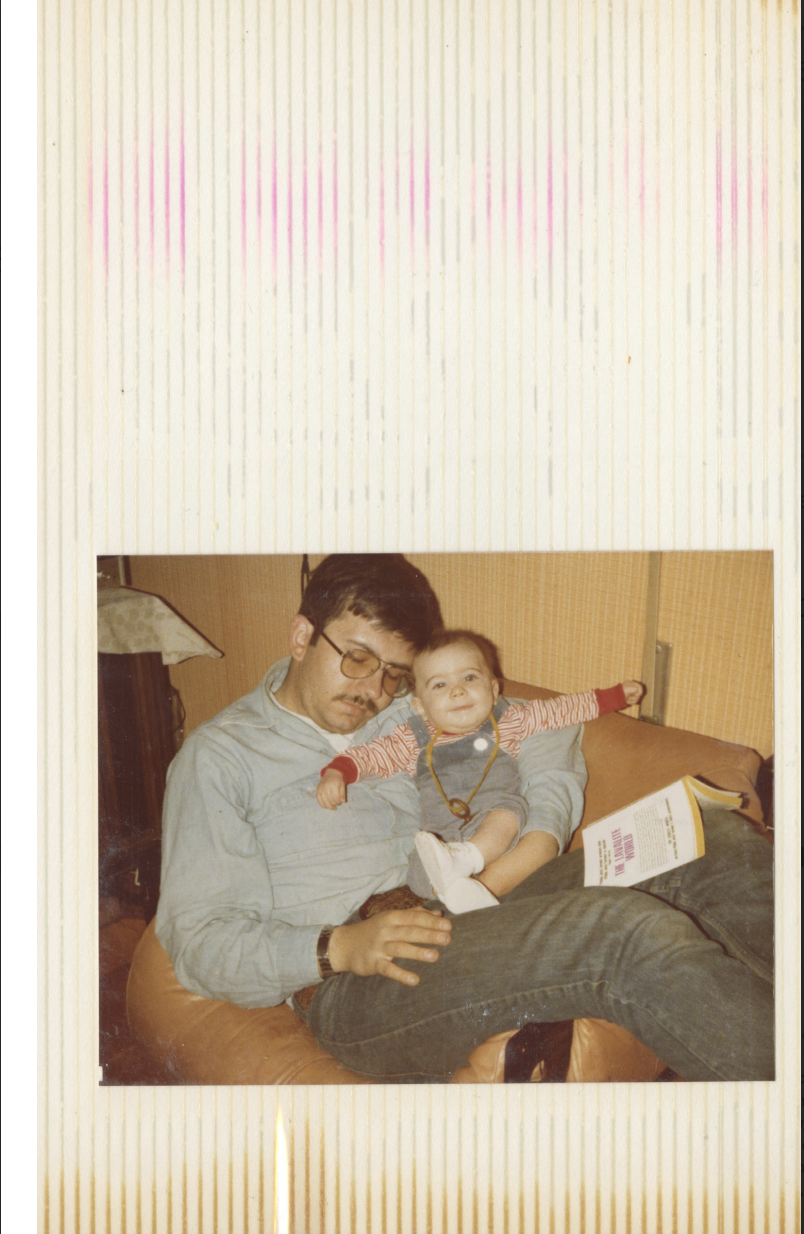

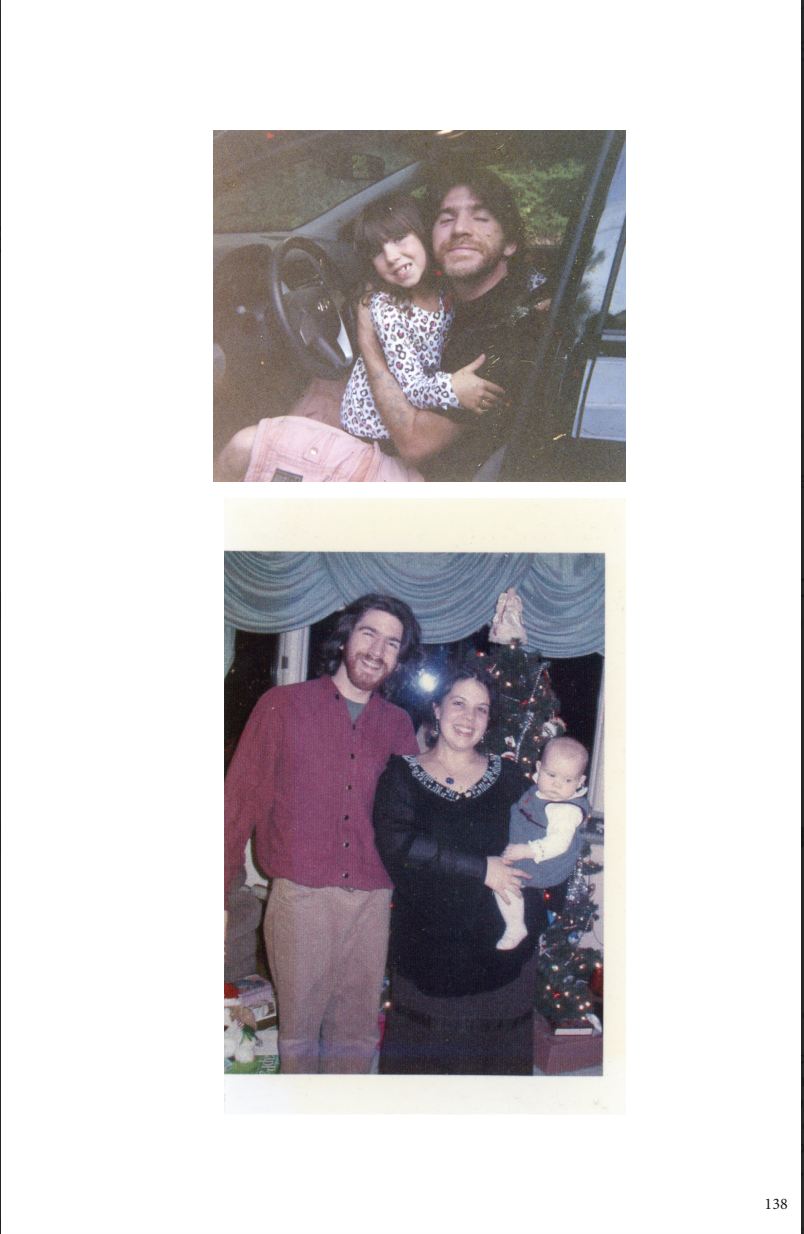

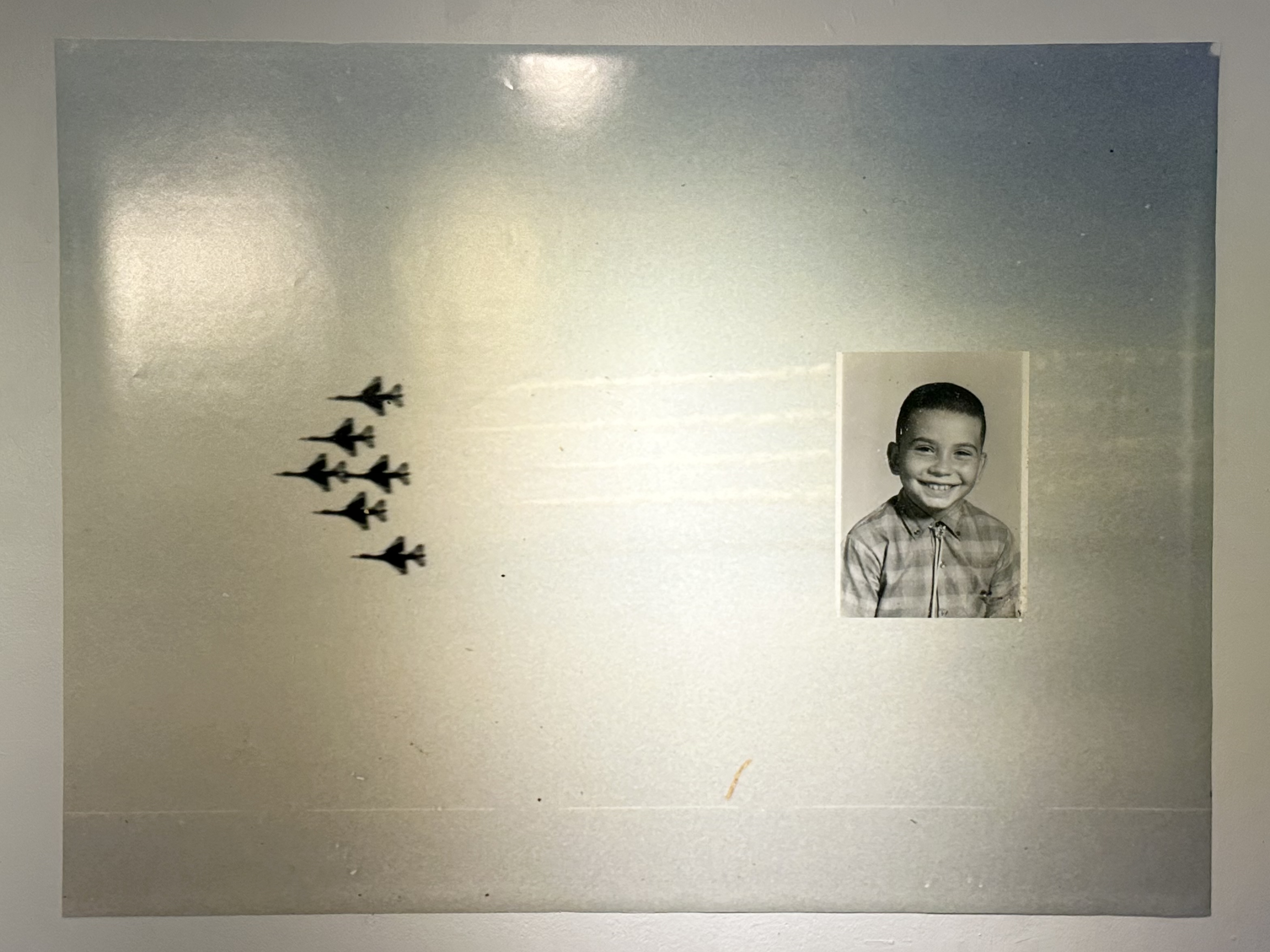

The exhibition features my family’s archival photographs alongside my own. On one end of the gallery, a record plays the Joni Mitchell album that inspired Barabara, my grandmother, to first tell Nick she loved him, surrounded by the sand dollars she collected at the various beaches they frequented. On the opposing wall are most of the remaining objects that Corwin, my father, has left of his father: a sci-fi novel, a knife, and two military pins. The photos (and archival video) portray various familial dynamics and contexts, evoking a sense of not only Nick’s personhood, but also Corwin and Barbara’s.

Scroll to bottom to view film Unsaid, Unseen

![]()

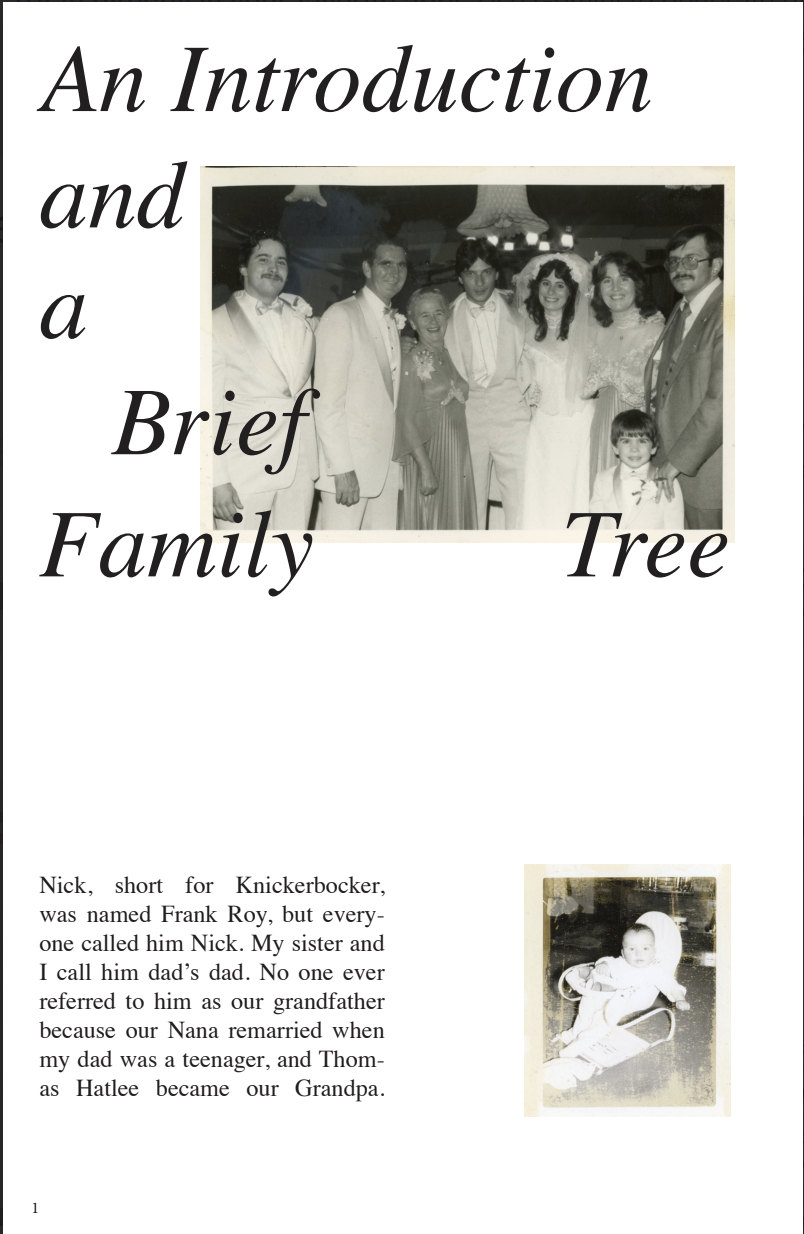

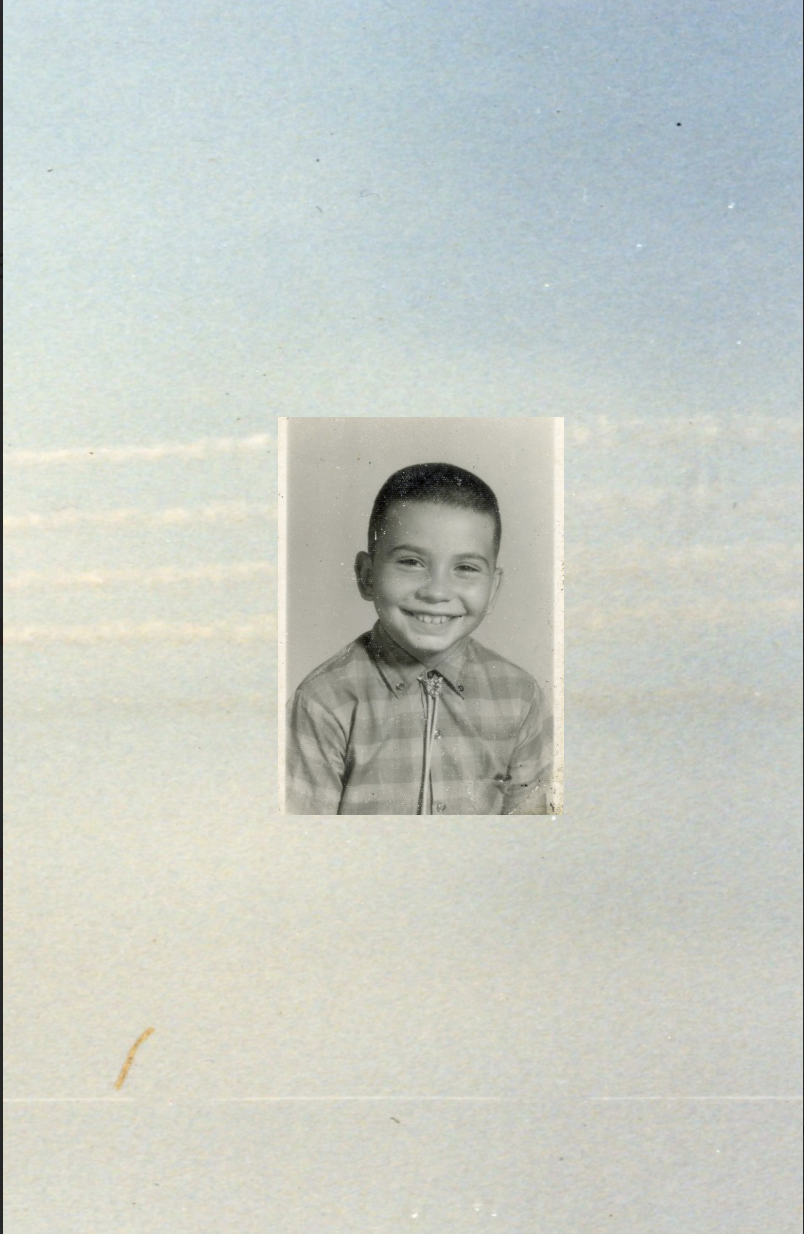

Nick, short for Knickerbocker, was named Frank Roy, but everyone called him Nick. My sister and I call him dad’s dad. No one ever referred to him as our grandfather because our Nana remarried when my dad was a teenager, and Thomas Hatlee became our Grandpa.

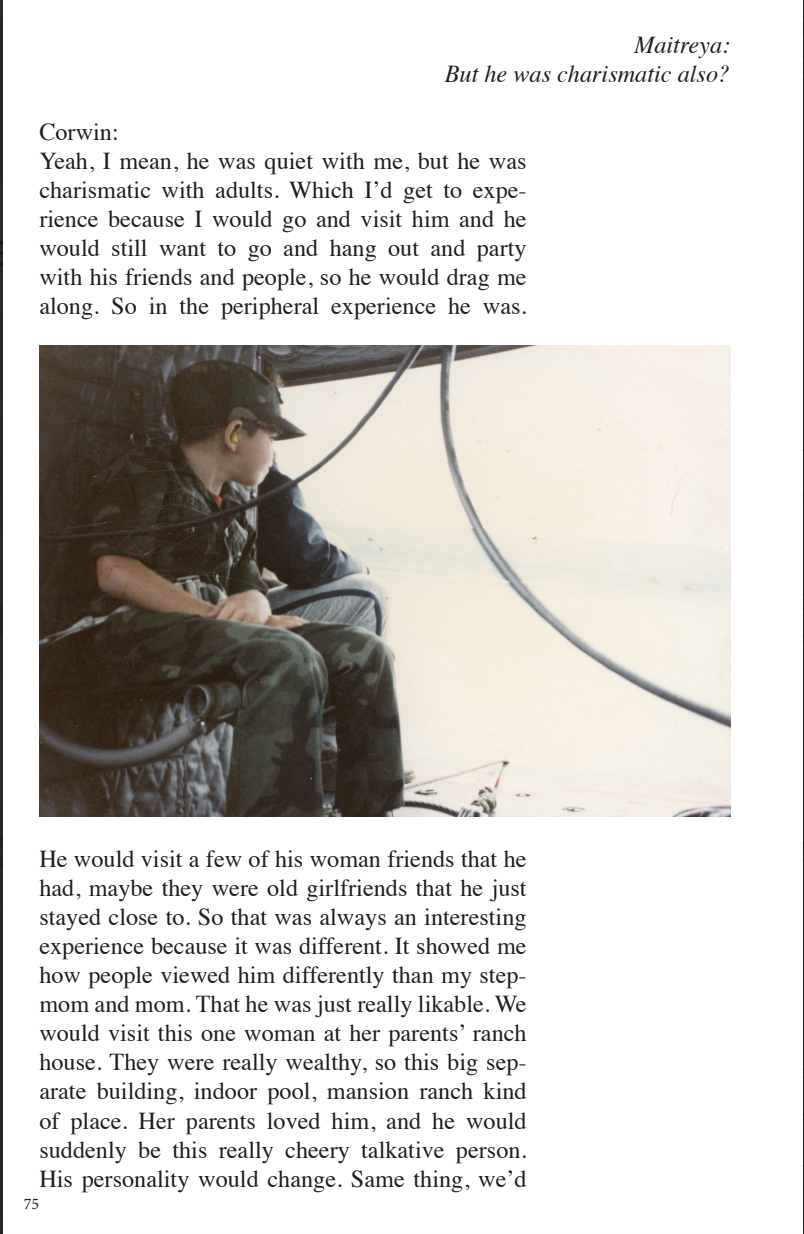

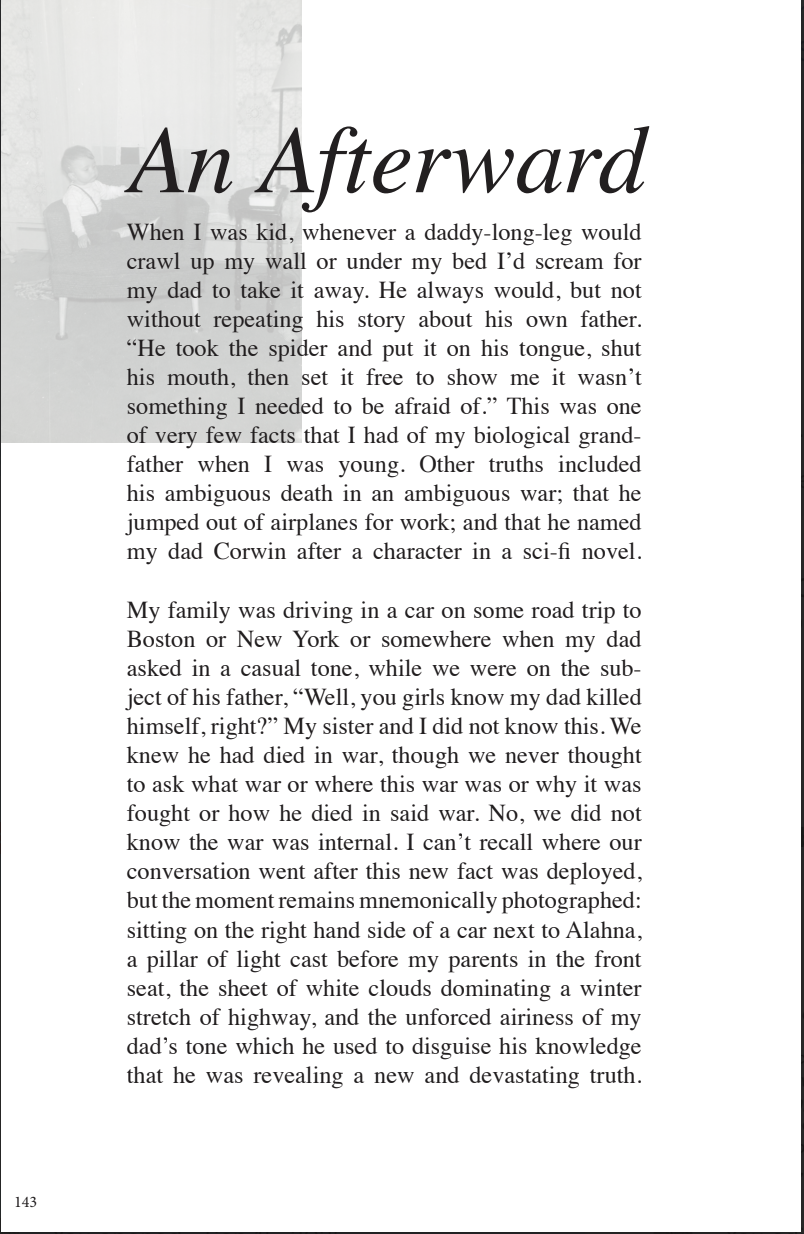

When I was child, each time a long-legged spider crawled up my wall or under my bed I’d scream for my dad to take it away. He always would, but not without repeating his story about his own father. “He took the spider and put it on his tongue, shut his mouth, then set it free to show me it wasn’t something I needed to be afraid of.” This was one of very few facts that I had of my biological grandfather when I was young. Other truths included his ambiguous death in an ambiguous war; that he jumped out of airplanes for work; and that he named my dad Corwin after a character in a sci-fi novel.

My family was driving in a car on some road trip to Boston or New York or somewhere when my dad asked in a casual tone, while we were on the subject of his father, “Well, you girls know my dad killed himself, right?” My sister and I did not know this. We knew he had died in war, though we never thought to ask what war or where this war was or why it was fought or how he died in said war. No, we did not know the war was internal. I can’t recall where our conversation went after this new fact was deployed, but the moment remains mnemonically photographed: sitting on the right hand side of a car next to my sister, a pillar of light cast before my parents in the front seat, the sheet of white clouds dominating a winter stretch of highway, and the unforced airiness of my dad’s tone which he used to disguise his knowledge that he was revealing a new and devastating truth.

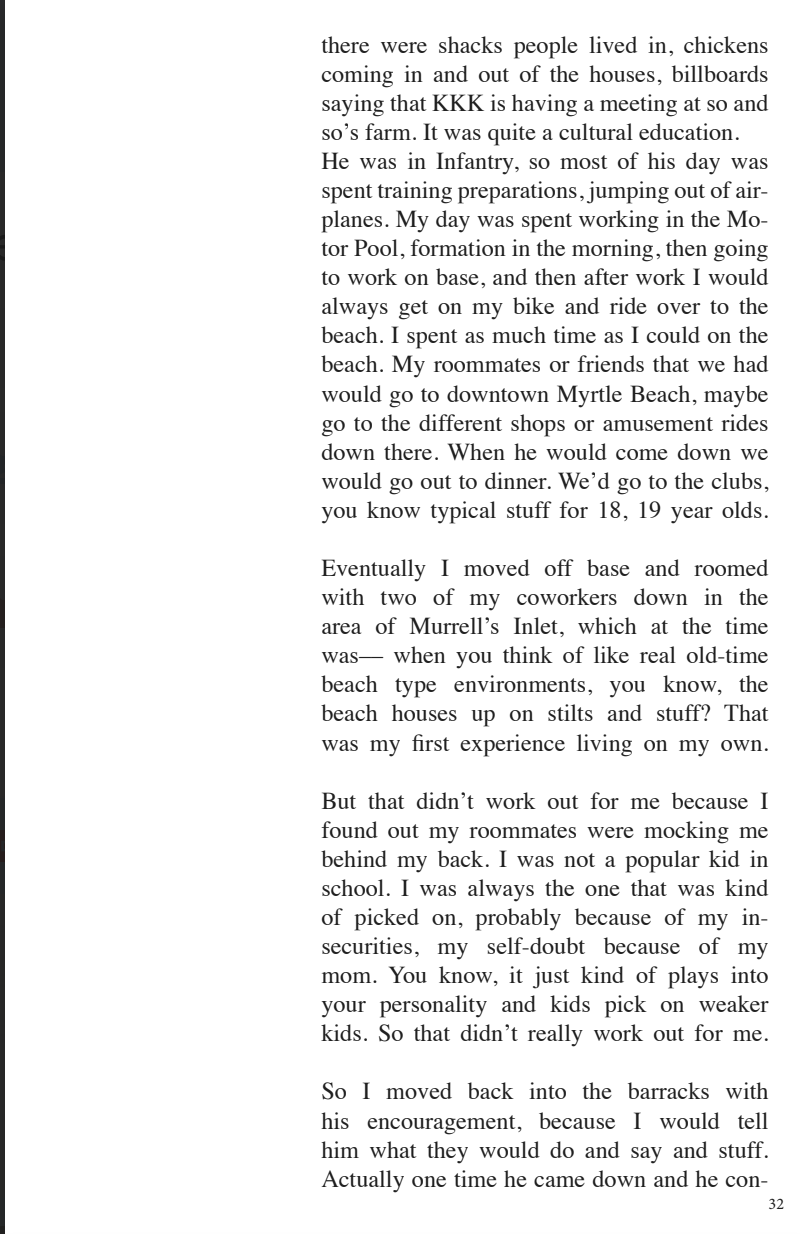

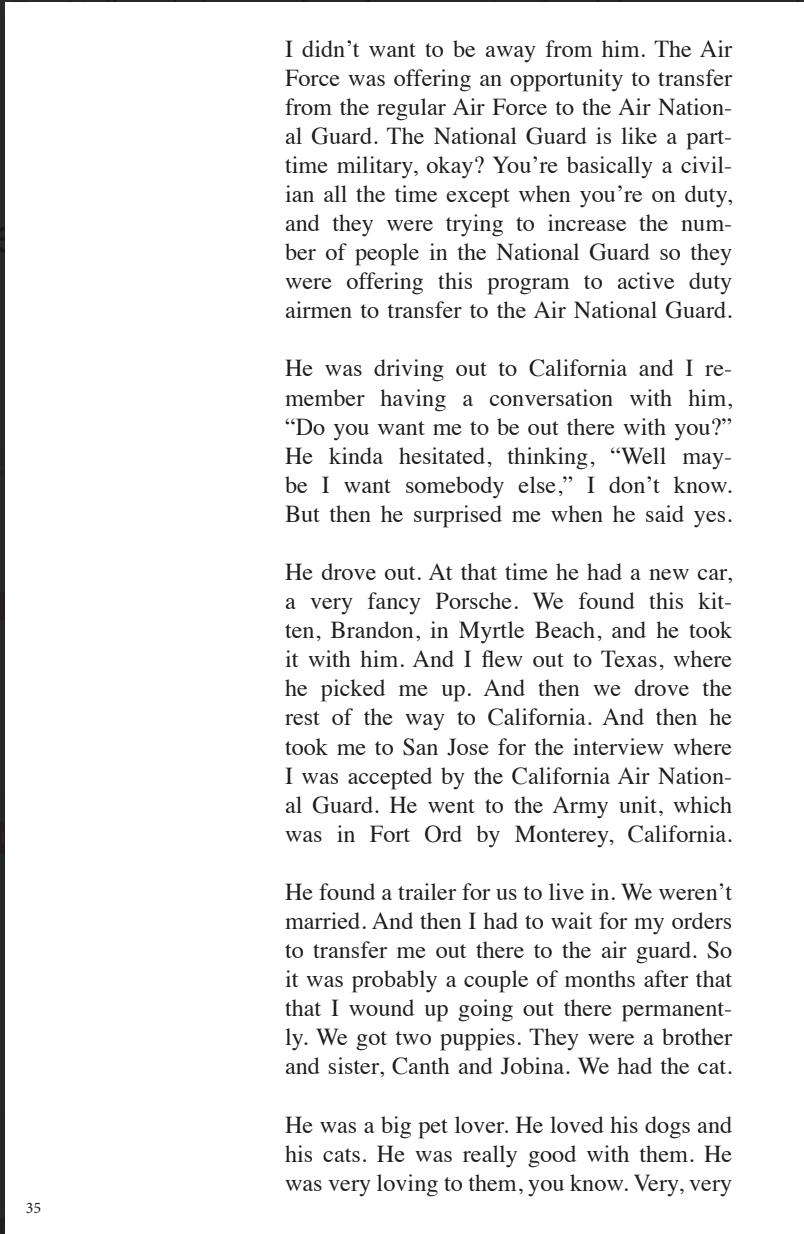

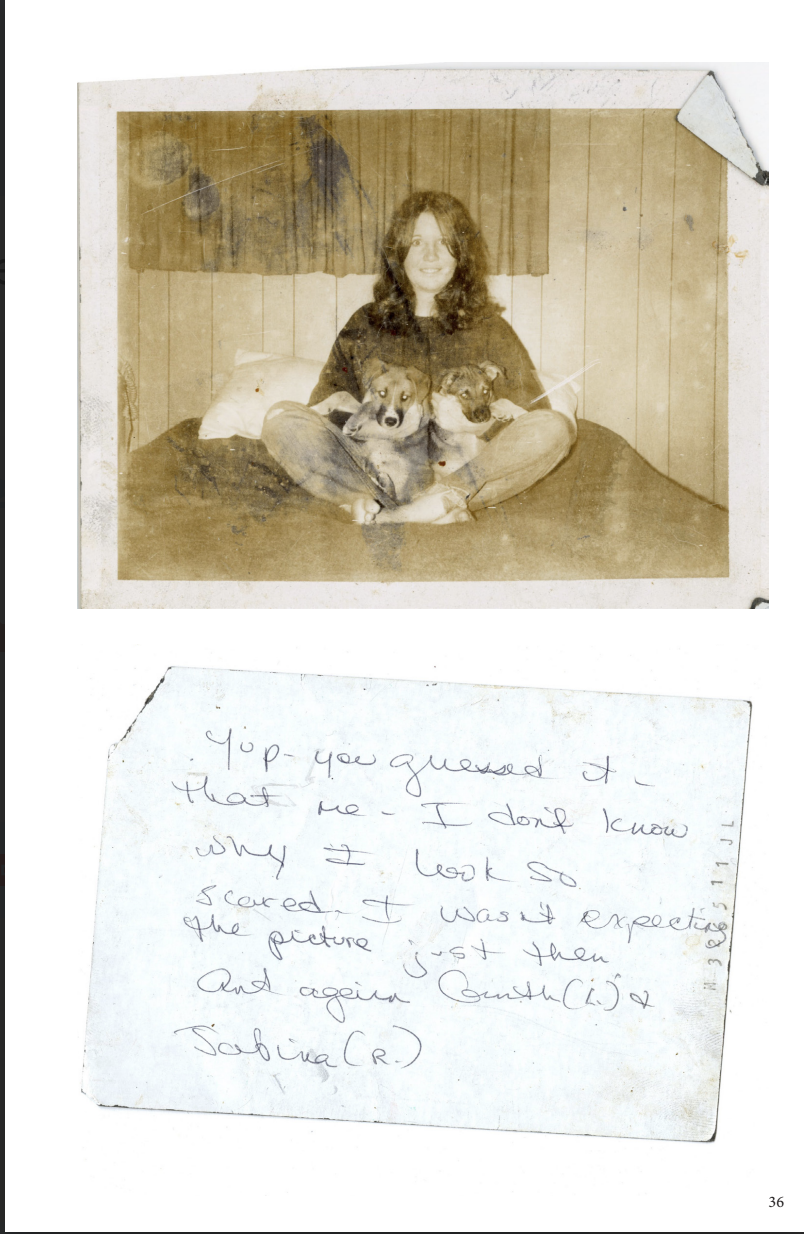

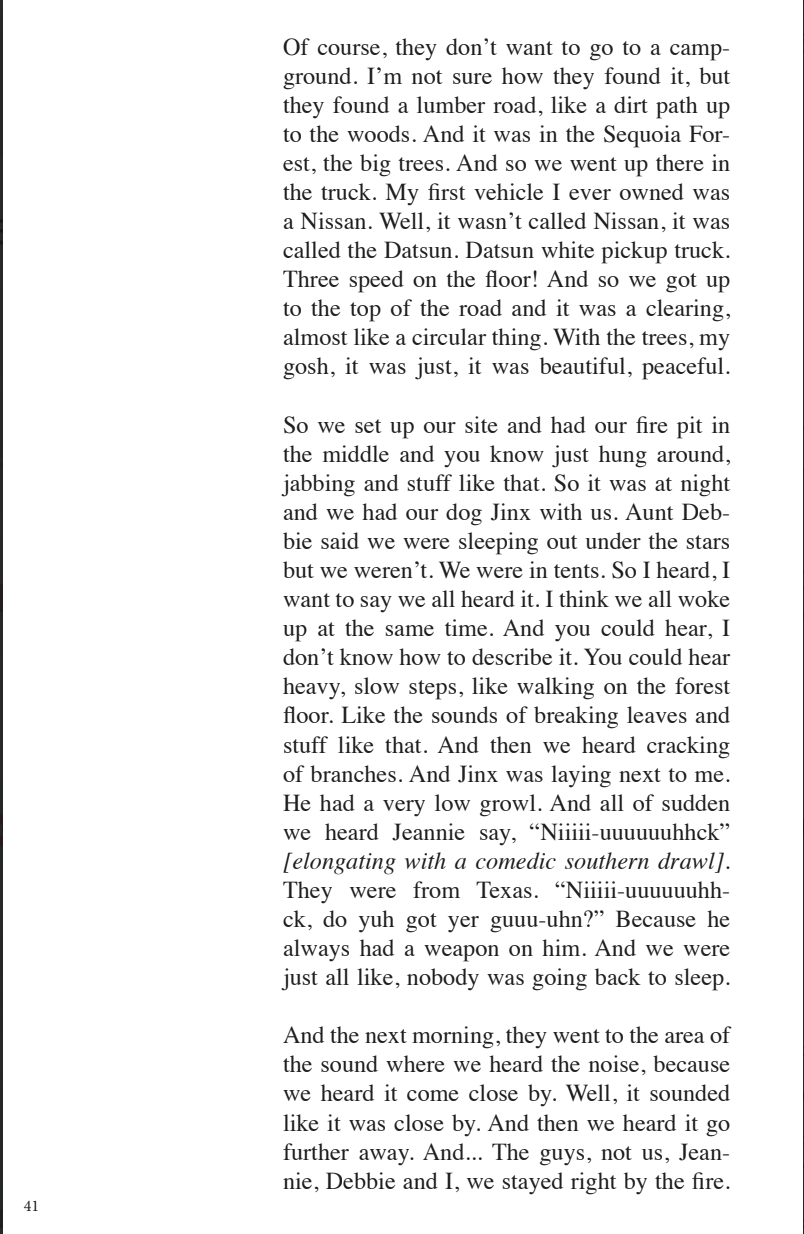

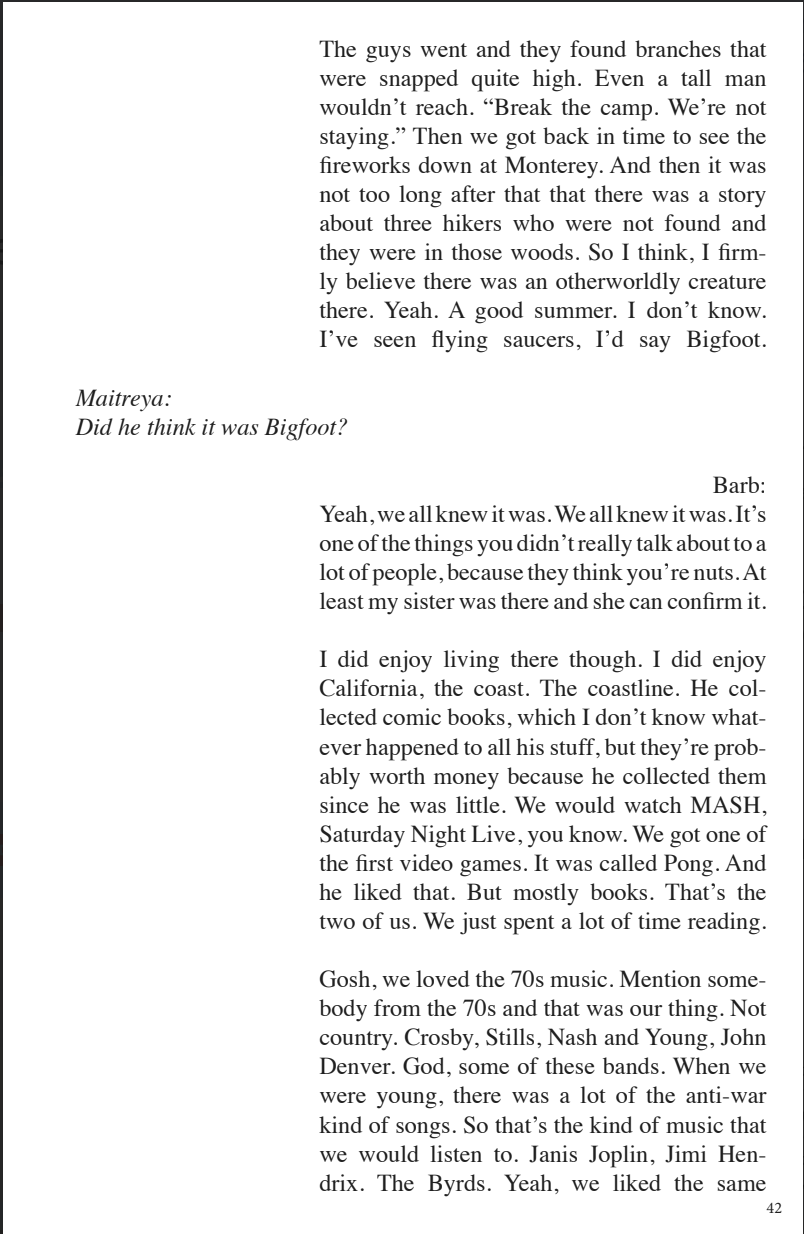

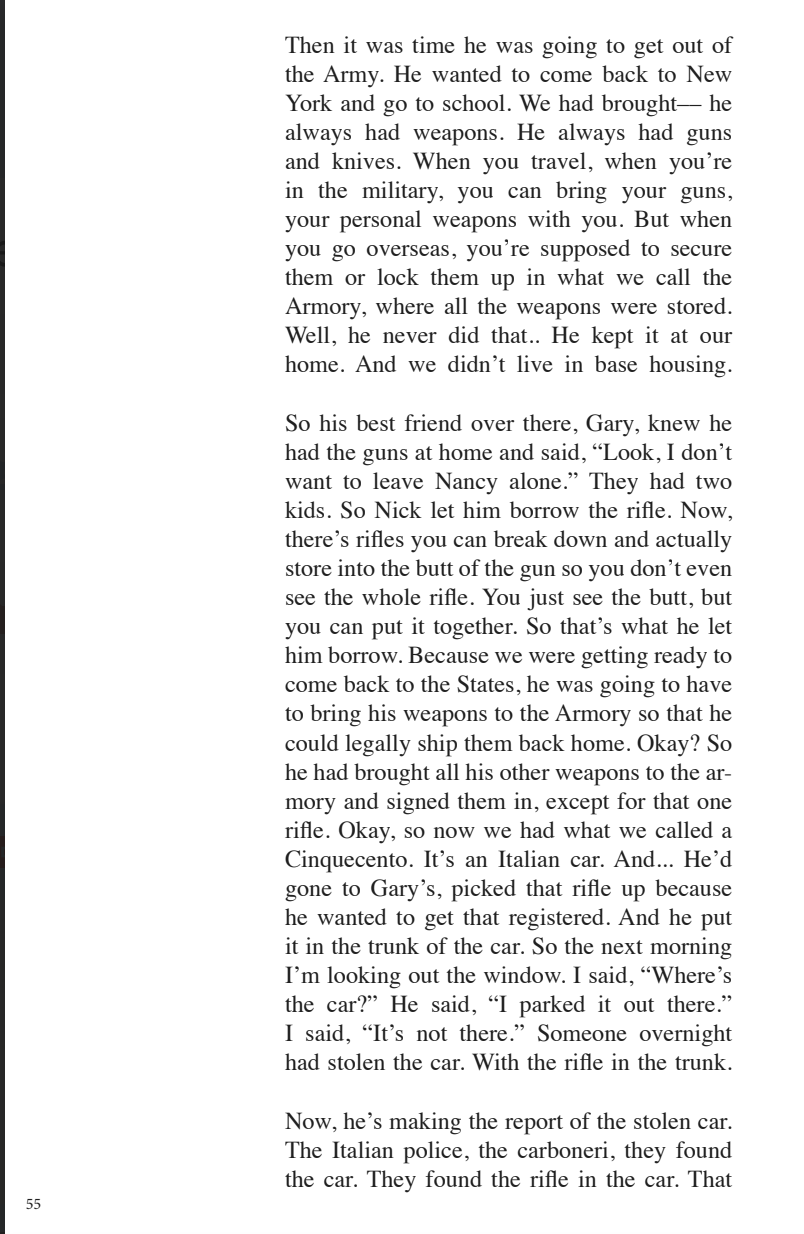

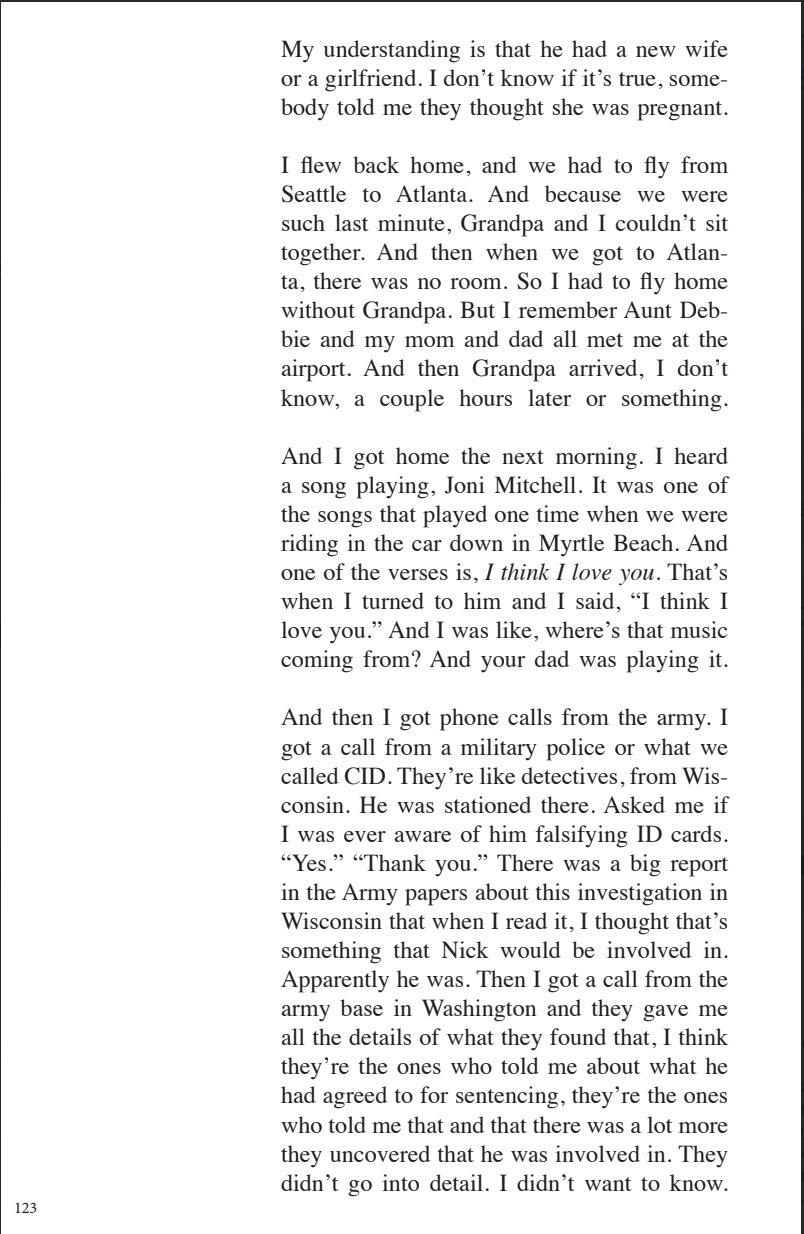

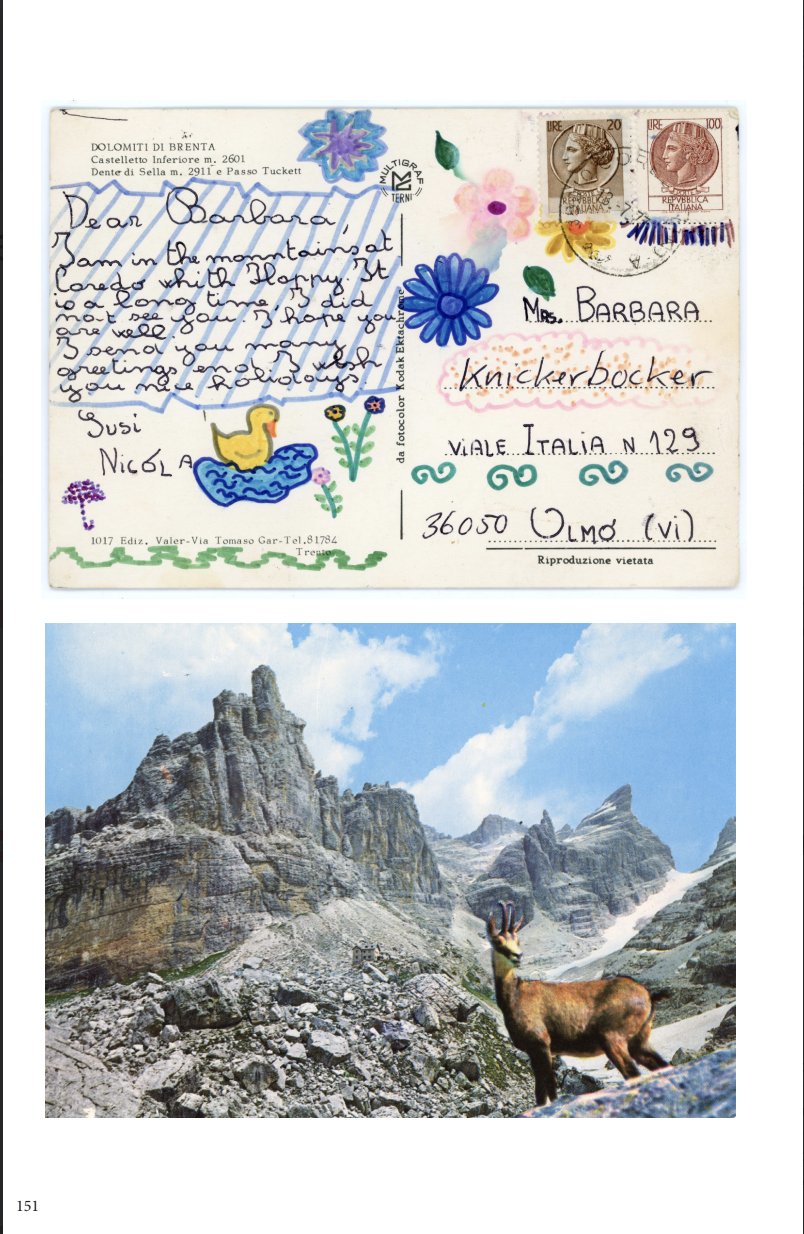

I never heard my Nana speak about Nick’s death. She would share stories of their time living in Vicenza, the military base in Northern Italy where my dad was born, and describe the beaches in Monterey or South Carolina where she and him fell in love. But these stories were never particularly personal to Nick. Her most told story, in which he was featured most prominently, was about their night with Bigfoot. When she’d relay the memory she’d use a drawn-out Texan accent, an impression of her friend asking, “Niiiii-uuuuuuhck…doya got yur guuuuyyyyn?”

Nick was buried in the National Cemetery, a two minute drive from the house my mom grew up in. Her parents still live there, so every Thanksgiving and Christmas and most summer days as children my sister and I played a stone’s throw away from his grave and I didn’t know this until a few months ago when we attended Grandpa’s funeral at the same cemetery.

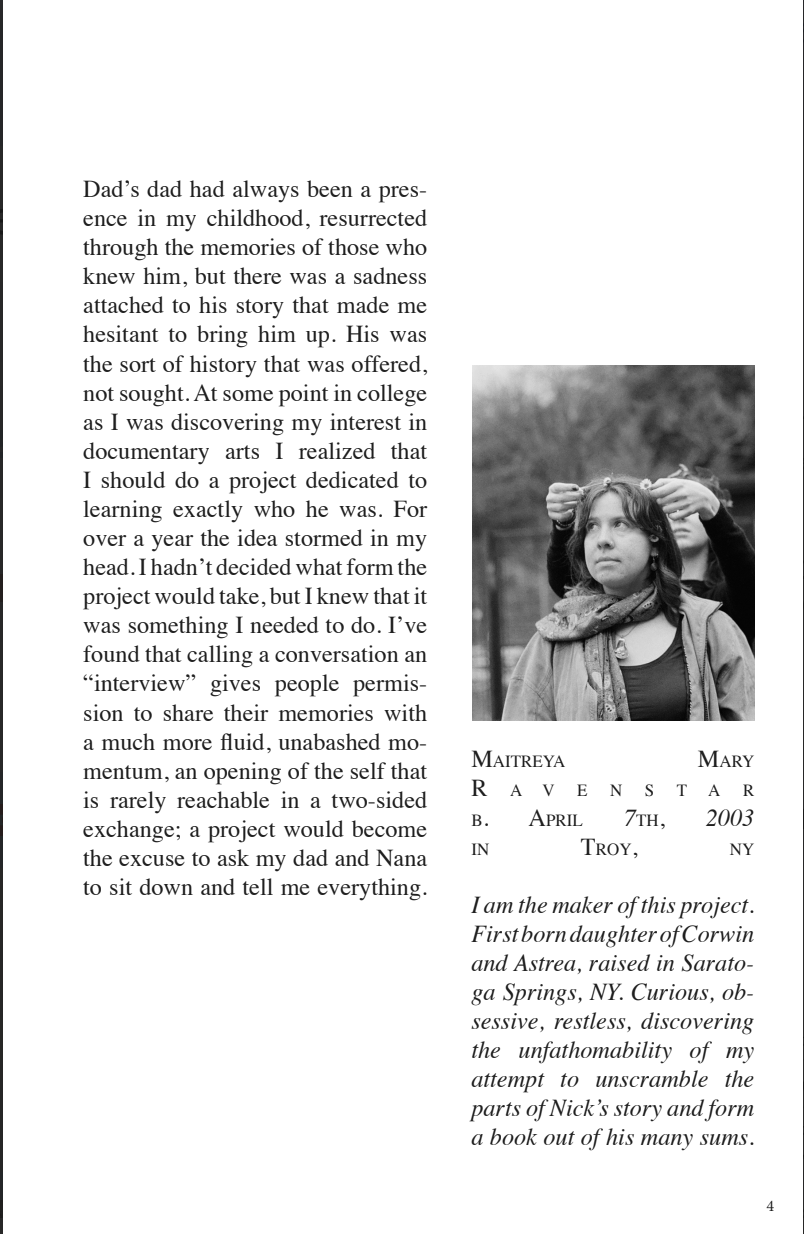

Though he had always been a presence in my childhood, resurrected through the memories of those who knew him, there was a sadness attached to Nick’s story that made me hesitant to bring him up. His was the sort of history that was offered, not sought. At some point in college as I was discovering my interest in documentary arts I realized that I should do a project dedicated to learning exactly who he was. For over a year the idea stormed in my head. I hadn’t decided what form the project would take, but I knew that it was something I needed to do. I’ve found that calling a conversation an “interview” gives people permission to share their memories with a much more fluid, unabashed momentum, an opening of the self that is rarely reachable in a two-sided exchange; a project would become the excuse to ask my dad and Nana to sit down and tell me everything.

I knew I was setting myself up for failure from the start. As much as I desired to learn exactly who my grandfather was, the impossibility of such an act weighed on me; I knew that the recollections of my dad and Nana would be contradictory, clashing perspectives of a son looking up to his military dad and a scorned divorcé who married her first love when she was barely twenty.

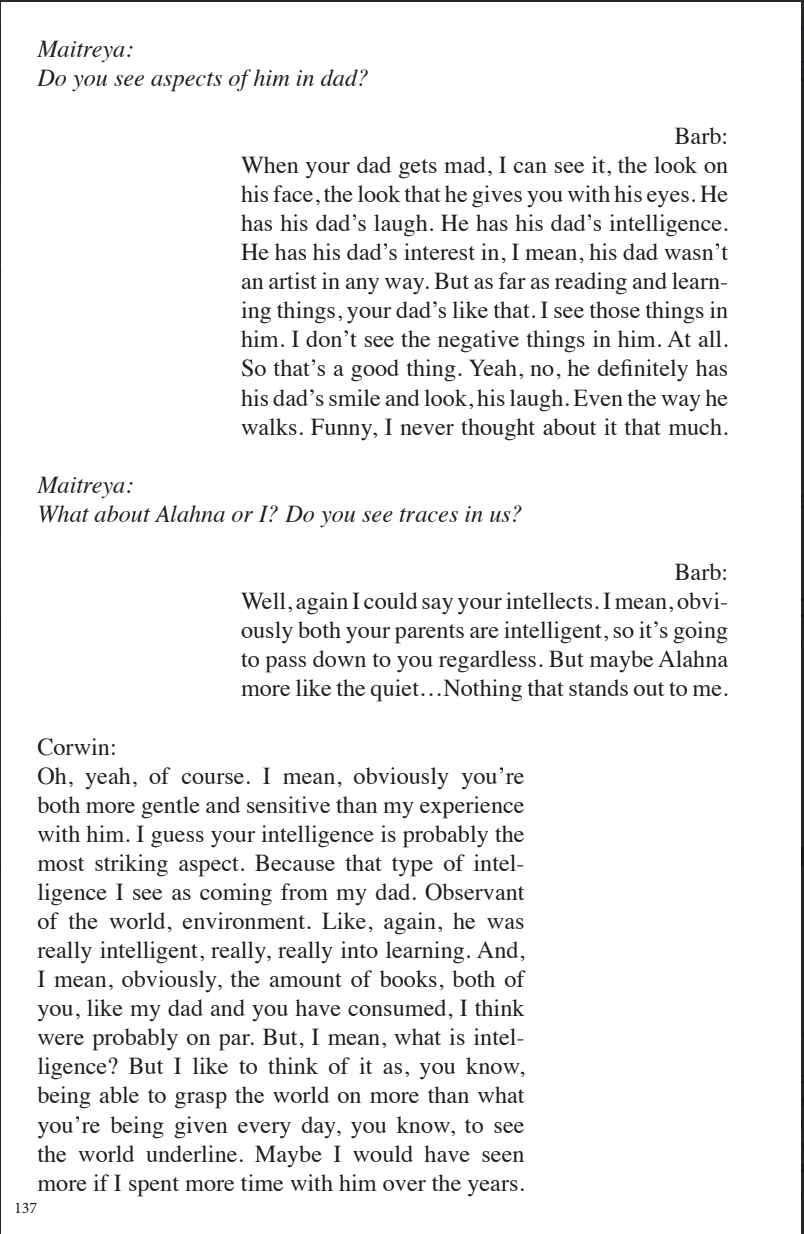

There is not a singular truth; rather, multiple simultaneous truths reflect my family’s individual perceptions. The memories of my dad and Nana tell a story about a son and a wife; they do not reveal why Nick’s behavior was so contradictory, why he was alternatively both charismatic and quiet, sometimes loving and others cold. My family’s stories portray their own truths, but not Nick’s. They are a smattering of learned myths from his childhood, a vivid portrait of him from nineteen to his thirties, and then a fadeout of brief interactions up until his death. So much is missing, and yet there is no one around to ask what about the rest? Here, I’ve collected the chapter of his life where he started a family, told from the perspective of the wife and son he’d eventually leave behind. How can that be a full depiction of a person? The deeper into this project I’ve ventured, the more I’ve realized I’m constructing multiple portraits; recorded here are the narratives of my dad and Nana, a son and wife with varying definitions of emotions, behaviors and words. Through the sequencing of this story, I have portrayed myself and my own perceptions and biases to a viewer too. Though he may be the subject, this portrait is not of Nick.

Both my dad and Nana keep reiterating to me Nick’s obsessive relationship with books. Their strongest image of him is him lying on a couch reading. Nana recently told me of his high school nickname, “Flash.” That his creative passion was photography and that he collected equipment in pursuit of image for many years. When I asked both of them, separately, if they see any aspect of his character in my sister or me, they confidently and quickly said his intellect, an eagerness to learn and seek knowledge, and I find the dominating emotion that rises in me learning of his life is not sadness or sympathy but disappointment that despite our shared pursuits, he assured I’d never meet him.

Paradoxically, if Nick hadn’t taken his life, my dad very likely would have remained in Asheville, North Carolina, which would have very likely set him on a different path that strayed from meeting my mom, which, very likely, would have ensured my nonexistence. This fact is a strange and wicked trick of time.

I wonder about what Nick would think of this project, and I hope he’d understand why I’ve pursued this question as a public project. Taking a private history, and investigating it publicly, has given me and my dad and my Nana the excuse we all needed to throw out the hesitation and completely dedicate ourselves to uncovering his memory.

When my parents, Corwin and Astrea, married, they didn’t take the name Knickerbocker. Instead, to complete their union, they formed their own name: Ravenstar. Corwin, originally Corvin, comes from the Latin term Corvinus, meaning Raven. Astrea, a self-given name that my mom found more fitting for her being than her birth-name Jessica, comes from the Greek Astraea, meaning star. They had me before they were married, and thus wrote Maitreya Ravenstar on my birth certificate before it was either of their legal last names. And so with the signing of a paper in an Upstate New York hospital, amidst a rare billowing blizzard in early April 2003, in the history of my family, I was the first Ravenstar to be born, and Nick was the last Knickerbocker to die.

Though he turned out to be the last Knickerbocker in my family, he may as well have been the last left in the whole of New York. The monumental head spinning, life altering realization that someone you love has taken their own life is a devastation that expands the width of all you know. Though he is enlivened through the stories which will continue to be retold by my dad, my nana, and now by me, indeed, for my family Nick is the last Knickerbocker in New York.

-Exhibition Wall Text

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

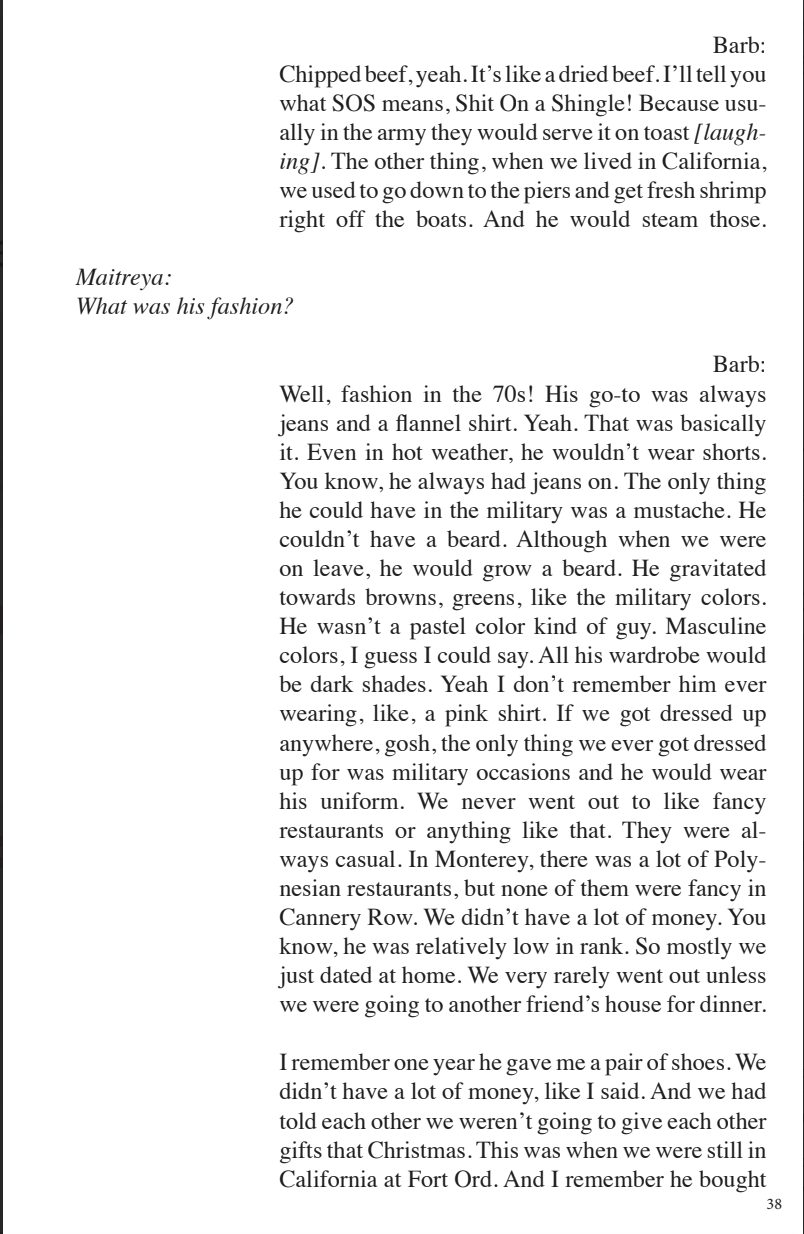

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()